Dr Rupy: Welcome to the Doctor's Kitchen podcast. The show about food, lifestyle, medicine and how to improve your health today. I'm Dr Rupy, your host. I'm a medical doctor, I study nutrition and I'm a firm believer in the power of food and lifestyle as medicine. Join me and my expert guests where we discuss the multiple determinants of what allows you to lead your best life.

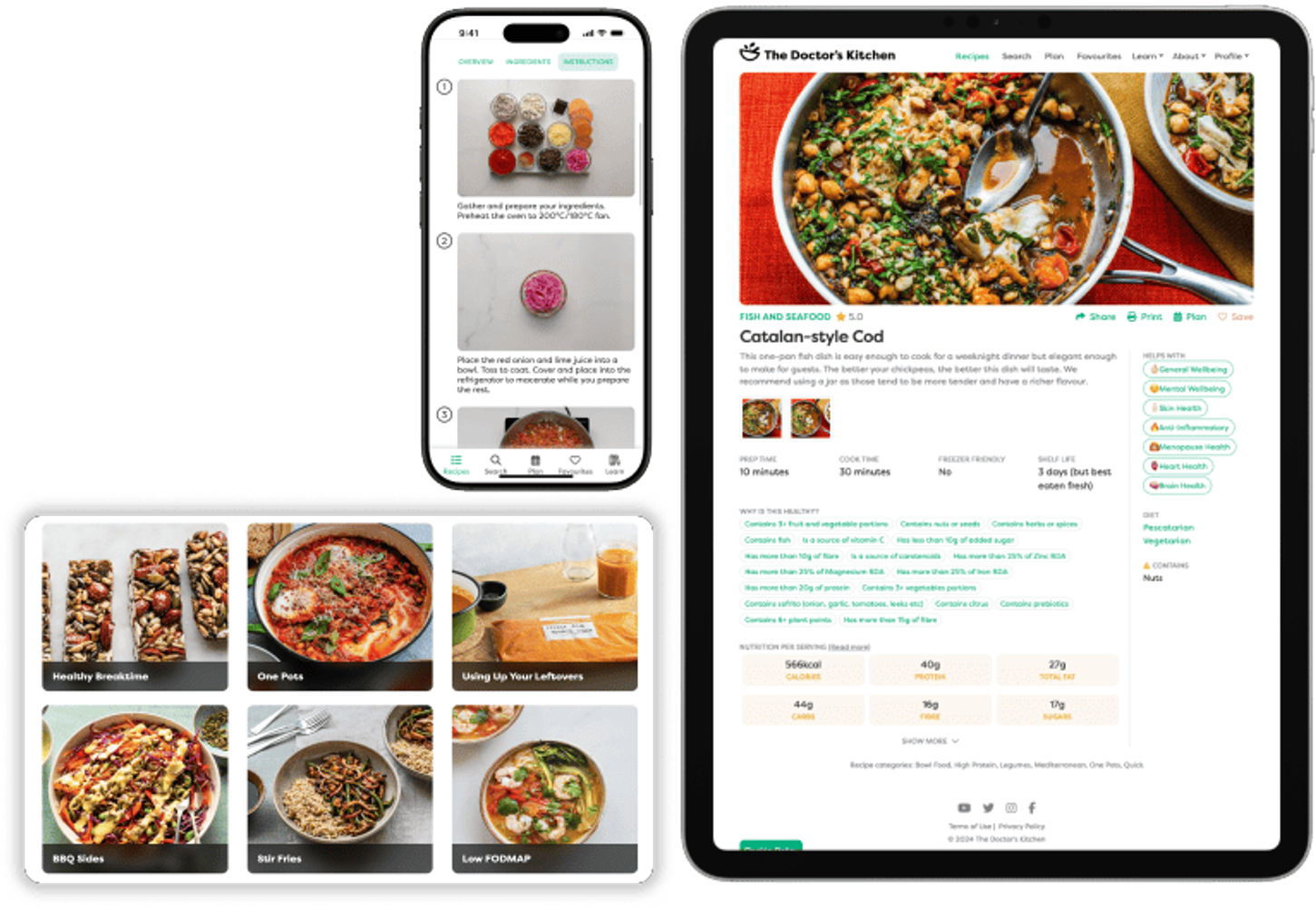

Dr Rupy: Hey, it's Dr Rupy. So we're going to be doing something slightly different this week. This kind of came out of a conversation that I had with my producer and I was explaining to him the podcast that we just released on Monday, the one with Mo Gawdat where we talked about the rise of AI. And he said, oh, that sounds really interesting, tell me about it. And I said, oh, well, basically, we are essentially creating another life form in artificial general intelligence that is going to be infinitely more powerful than us, have much more processing power such that it can actually make sense of the millions, if not billions of different sensors looking at weather, temperature, environmental change, sensation, all these different things. And so basically AI is going to take over all our jobs and and basically be top of the food chain. And and his response was, so you mean to tell me I've just edited a podcast episode on how the likelihood of me being infertile has risen over the last 50 years and now machines are going to take over my jobs. And so to the to the to his point, you know, we've done two back-to-back pretty scary podcasts. So I thought I'd take a break from the frightening realities and actually bring some humour and some personality back into the pod this week. So this is just going to be me this week, talking to you about a few things that I think you might find interesting, some interesting articles, some questions that I've had in the past. We've done a couple of episodes like this before. So at the start of the year, when I launched the book 321 and also when I did my 100th episode and I basically talked about the four formulas for lifestyle that everyone should know. And those were super popular and I don't I don't really understand why. I mean, I like to think that I'm getting better as an interviewer and bringing on true expert guests that have dedicated years of research into nuanced subjects where they can speak on the manner on the on the matter in a much better way than me. But for some reason, people like me talking to the mic and and giving you guys some some tips and and some of my gems of information, I guess. So I'm going to try that this week and and do let me know, you know, if you think this is complete rubbish, then send me a message on social media or via the newsletter. There's a feedback tab that we've got there. Or if you want to hear more of these on different subject matters, let me know and I can I can do it again. But we'll see how it is. So there's a few things I want to talk about today. I want to talk about what my information diet is like. And an information diet, I think is something that we all need to pay a bit more attention to because with so many sources of information, so much opportunity to influence our brains and our psychology and and truly what we think about, I think we have to be very mindful about the sources of information and what we expose ourselves to on a weekly basis. I've got a couple of papers that I've read over the last couple of weeks, and as you'll hear in my information diet, I tend to read a couple of papers a week, usually in preparation for a podcast, sometimes in preparation for a talk or something like that, or something that's come out of my clinical work that has sort of sparked some interest. And yeah, hopefully you'll find those papers super interesting. One of them is about the microbiome as a an opportunity to combat depression specifically during the COVID-19 pandemic. It's more of a an editorial review rather than a primary research per se. Another one is to do with cheese. And it says a lot about nutrition science overall and and how the media can hype things up. This is a paper that was picked up by a number of different news outlets just last week. And in not as as much of a fashion of the whole butter is back time magazine piece that kind of put the world upside down. It it's it was veering on that in terms of cheese. And I just want to clarify a few things about the research and actually what the author said about their own paper as well. And if we have time, we can talk about the portfolio diet, which is this diet that is meant to be associated with better cardiovascular outcomes and and also whether vegans are happier. So if we've got time, I don't want to talk for too long, but those are a couple of papers that I want to talk about today and some interesting tidbits along the way about how I do things and how I approach things too. All right. So my information diet. If you're a subscriber to the newsletter at the doctorskitchen.com, you'll know that every week I post something to eat primarily, you know, the Doctor's Kitchen is all about delicious, flavourful food that's truly good for you. So we have we we've been teasing some images from the app that I've been painstakingly building for the last two years. We've been doing some primary research, interviewing potential users, developing the designs and actually building this platform from scratch as well. There's there's a few easy ways in which you can do it. You can white label a product. So this is getting totally off topic here, but you can white label a product so you can look at something that already exists and just slap your name on it and then add a few recipes. What we're trying to do is actually build something from scratch. So essentially what it is going to be is like the head space for healthy eating. I've hinted at this before. We're massively delayed. We should have been launched already and and trialling stuff on there. But it's going to be a selection of recipes that you'll be able to filter according to your health goals. We have our academic team that has been going through thousands of papers, all the different literature looking at diets for cardio protection, brain health, inflammation lowering, as well as just general wellbeing as well. What are the best sorts of diets out there and how can we coax people to eat toward a pattern of eating that actually supports you and your and your health goals and also, you know, what are your dietary preferences and intolerances. I can't remember where I was going with that, but basically, I've been busy behind the scenes, beavering away on this product. And we've been releasing images from it on the on the newsletter. But the other things that I do on the newsletter are things to listen to, watch or read. So it's eat, listen, read or some weeks it's eat, watch, listen or whatever I'm doing that week. And a theme that you'll you'll come across quite often whenever I write the newsletter and they're quite short newsletters because I'm time poor and I know the best newsletters that I get are ones that get straight to the point. You know, look, I'm in the middle of work here. I don't want to be disturbed. I don't want to be taken on a rabbit down a rabbit hole where I completely lose and I procrastinate. So just give me your three things that you want to say to me and and let me get out. So a common theme is that, you know, we have to be very mindful about where things take our mind, what we allow ourselves to be distracted by. And so I'm I'm getting a little bit more rigid is probably not the word I'd use, but I'm definitely getting a lot more mindful about what sources of information I want to feed my brain. I rarely watch TV, I'll be honest. When I did the show with Prue Leith in it was it was aired in June. It was recorded in in February. That was probably one of the only times that I actually used my television and and jumped on channel four or whatever. You can still find it, I think on channel four. And so yeah, so I I rarely watch TV. My information diet is broken into three main things. So I read about one to two books a week. That sounds like a lot and it it is a lot. I'll be honest, it is a lot. But that also includes a lot of the preparation that I do for podcast guests. Case in point, when I interviewed Mo this week, the episode that was out on Monday, it's a very different episode, by the way. So if you haven't listened to it, I highly recommend you do listen to it because it's slightly left field, but it's it's going to impact all of us over the next eight, nine years. So please do give it a listen and I think we all need to be prepared for it in the same way we need to be prepared, we should have been prepared for a pandemic. But case in point, I I read that book and I I speed read it. So, you know, rather than having a leisurely read, you know, sat by a beach and then reading your book and getting lost in it. I I have to almost study a book. And whilst I'm reading the book, I'm also thinking about questions. Oh, that's an interesting angle. How would I interview this person? You know, what what kind of information what kind of parts of of the informative parts of this book would I want to share with my audience? How would I bring this into conversation naturally? I don't want it to sound too contrived because a lot of the podcast is actually quite off the cuff and we we go down different avenues as the podcast progresses. And I think that's what's so beautiful about the medium of of interviewing in this style. You know, we don't when you do live TV, it's very regimented. It's like we're going to hit these three points and we want to do it on on like in 45 seconds and we have because we've got another VT to so so it's very different, which is why I love podcasting. But yeah, so I I listen, I I I read at least one to two books and that's that's not only sorry, reading, it's also listening as well. So another case in point, when I interviewed Professor Swan, who was the the author of the book from the previous week's podcast talking about the rise of fertility issues and what could be potentially causing those. I I listened to that book as well as reading segments of it as well. And a top tip, sorry, I'm going in different directions here, but a top tip is if you do have an audible or another sort of audio subscription platform, I use audible, there's no commercial ties there. And you want to get through a book fast. Here's a hack that I've learned along the way. So it it it's twice the price, so it's only for a few books and if you're studying for something or if you really want to get through something quick. So I listen to podcasts on 1.5 or two times speed. It's really weird. It infuriates my my my partner. I can't listen to podcasts out loud. I have to listen to it on one speed with her. But I I I listen to to podcasts on on double speed because I I want to get through the information and I I I can I've actually, you know, found a way in which that's fine for me. I've gradually pushed myself up from one to 1.25 to 1.5, etc. But one thing I've I've tried doing in the past and it works really, really well is if you listen to it on two speed or 2.5 speed or even three speed if that goes up on your podcast player and you actually read the text at the same time, it reduces the likelihood of you procrastinating and moving your eyes off the page, which happens, I don't know if this happens to everyone, certainly happens to me a lot. So what what happens is it just super focuses you into this book. And it's one of the things that I did with Professor David Sinclair. So Professor David Sinclair has been on the podcast before. He is the guy that popularized resveratrol. He is a Harvard geneticist and he wrote a fantastic book called Lifespan and it and it chronicles a bit about aging research and Professor Horvath and and how we've used C. elegans and a whole bunch of other species to study aging and try and reverse the biological clock. But his book is very, very technical. And so what I found is I listened to the book and I read the actual physical text at the same time and wow, I absorbed so much information because I had it coming from two mediums, my vision, my my ears and it kept me super focused. And so if if there's anyone who's who's trying to hack a way of absorbing information quicker, that's one of my top tips. I I think it's brilliant. Obviously, you can't do it all the time because you're basically paying twice for the same material. But if you need to get something through something quite quickly, then that's then that's what I would suggest. Anyway, so that's that's one to two books a week and that's both reading and listening. One of the books that I'm reading at the moment actually, which isn't anything to do with who I'm going to be interviewing, is The Monk Who Sold His Ferrari. And if if you've heard me talk about the subjects before, the 5:00 a.m. club is something that really influenced me and it's something that I try to do as much as possible, waking up at 5:00 a.m. before anyone else is up and giving myself an hour where I can focus on things like meditation, affirmations, journaling, as well as exercise, and whatever else I need to plan for that day and it just sets my day up amazingly well. This is by the same author, Robin Sharma, who I'd love to have on the pod actually at some point in the future, who wrote this pretty revolutionary book back in the late 90s. And his books kind of follow a very similar theme. It's they're more like novels, but they're written in such a way that you absorb a lot of the information that he's trying to get across. In this particular book so far, it's about spirituality. It's about recognizing that your awareness is the most important asset of your brain that you have. So actually being aware of awareness is is super important. It's actually very similar to another book that I am concurrently reading by Rhonda Byrne, who you might remember wrote The Secret. Her latest book is called The Greatest Secret and it's it's it's very similar in in the same vein. So and and I think this ties in quite nicely with the subject of your information diet and how important it is. So anyway, those those are the couple of books that I'm reading at the moment, plus a couple of other books that I'm preparing podcasts for in the future, which I think you're going to find fascinating. All right. So the the other parts of my information diet and a big way are podcasts. So and no, I don't listen to my own podcast. That'd be weird. I obviously listen to it to to edit it and all the rest of it. But I listen to a shedload of podcasts. It is my preferred medium of information. I can get completely lost in it. I can do things like walk my dog, go to the gym, doing housework, cooking, like I just love listening to podcasts. And I listen to a few different things to keep myself out of thinking about work the whole time. So yes, I do listen to some nutrition podcasts. The ones that I listen to are fairly technical. Peter Attia's The Drive podcast, which is generally about aging and longevity. Those are his sort of niches that they they they go for, but they they do expand their topics as well. Like they just did one on 9/11. They've done some on psychology, which I think is very related to longevity actually and and stress and happiness. But they are deeply technical and three hours long as well. So it's it's not for the faint-hearted. Other nutrition podcasts, one I I started listening to recently is with Dean and Aisha Sherzai. And if you remember those those guys were on the pod a few weeks back. They're neuroscientists who've done a lot of research as it pertains to Alzheimer's and dementia prevention. We had a wonderful conversation and they've been doing a podcast for a couple of years now. I'm going to come back to that because I I think they they said some really interesting things that I want to talk about just before I start talking about the studies. But yeah, so I I listen to a range of of pods in the nutrition space. I listen to a lot of tech podcasts. It sounds weird, but I think obviously because I'm doing my app and I want to learn about the the commercial aspects of creating an app as ambitious as the headspace for healthy eating. You know, what I'm trying to do is bring the power of food to a billion people worldwide. And in order to do that, I need to learn a lot of things in a space that I'm not very comfortable with. So I listen to I've started listening to one called My First Million. It's basically two guys who have exited companies, have been, you know, very financially paid off and they started a podcast where they just talk about ideas every week and it's it's absolutely brilliant. So they that podcast is actually quite inspiring where they just talk off the cuff and they just talk through things. And I think that's it's it's quite relaxing if I'm honest, just to listen to two people have a genuine conversation where there isn't much of a script. And this is what we we're trying to do with the Doctor's Kitchen podcast as well. It's it's very it's I I want to give the impression that it's relaxing. It is quite it is very relaxed if I'm honest. We have a few points that I've got on my side, but generally we don't really script anything at all apart from the intro and outro and that's it. A lot of the podcasts that I I listen to also, they dip into a bit of politics, usually US focused politics, but they talk about the issues between power struggles, China, Russia, America, basically the West and East as sort of been the paradigm for for many hundreds of years. And it's been exacerbated by the pandemic. So I I'm I I it's quite it's quite if I'm if I'm honest, those aspects of what I listen to are quite scary because you're just always wondering about the future, but I like to be quite informed and I think being informed for me, at least anyway, is is quite empowering and I and I quite I I I find that quite settling. And on that, using that as a as a flavour for for the other things that I listen to, I've started listening to one called How to Take Over the World. And it's a history podcast and it's absolutely fantastic. So I've listened to two episodes. One is on Thomas Edison and his prolific career as a as an inventor and how everyone knows him for the light bulb, but this guy was a genuine entrepreneur. He had no formal scientific background. He never went to university. He was basically a tinkerer and a leader and someone who's just absolutely passionate about creating things constantly well into his later years. I think he he lived for over 80 years. And the the podcast itself, how to take over the world, is just very well done. It's a historian who does a lot of research for all the episodes and it's it's literally just him talking through stories. And I think, you know, there's so many parallels between what what we're seeing today with the rise of China and the rise of the West and and all these different power wars that are going on and what we've seen in the past. And I think, you know, I'm not specifically referring to Thomas Edison. I'm actually referring to another podcast episode that he's done all about Napoleon. I'm not a history buff at all. And I think if when I was a child, my history teacher had have been telling us stories in the same way that the podcast host Ben, I forget his surname, does on this podcast episode, I I think I'd be absolutely enthralled. I might have even gone into history because it's it's that good. So definitely go check it out. That's my my top tip for for podcast. If you're interested in tech, listen to my first million. I also listen to how I built this. It's one of my favourite podcasts. Again, it's all about stories, about human connection. And if you're interested at any point about historical figures, then how to take over the world. It's not a very big podcast at the moment. I don't know how many listeners they've got, but it's it's very, very small, but it's done very, very well. The the next one I'm going to listen to is on Steve Jobs as well. But there's a whole bunch of other characters from from history, some of whom that I don't know, I'll be honest, but I'm definitely going to listen to it because anything that this guy puts out is is awesome. Another important facet for my information diet every week. So we've we've got books, we've got podcasts. I want to talk about things that I exclude. I try and limit obviously social media as much as possible. I sort of post, engage in the community, comments where I can, respond to messages if I can. We get inundated with messages and a lot of the time it's asking for advice, which you can't do. But I I limit news feeds. So I used to have my homepage as a as a news feed, whether it be BBC news or MSN or whatever it might be. I don't do that anymore because if you notice, if you look at any news page, I mean, go go and look at one now. Usually the top three articles are going to be very, very negative. And that changes your psychology in a way that is detrimental to you. And I'm not saying that we shouldn't be aware of things that are going around in the world. Obviously, we need to be conscious and and fully cognizant of things that are going around us, but when it impacts your psychology to the detriment of of you, then that's not serving you. It's not serving anyone if I'm honest. So I've stopped with the news feeds. There was a YouTube TED talk that I shared actually about the media specifically. And and you know, I've done it for a long time now where I don't have a news browser and it's it works very well for me. One of the things that inspired me actually to talk about my information diet this week is going back to that podcast, how to take over the world with Napoleon Bonaparte. There was a a section and I'm going to share it on this week's newsletter. There's a there's a section where he talks about Napoleon's ability to compartmentalise his thinking. And the analogy he uses is that of a a desk with a bunch of drawers. And he's quoted as saying, you know, if I if I'm if I'm thinking about one thing and I I need to stop thinking about and then and divert my attention, you know, to issues within the military or issues within economics, I close that shelf, that drawer, sorry, and then I open the other drawer. And so and that describes his his ability to focus on individual things one at a time. There's no point of having all the drawers open at the same time. And he's also quoted as saying as another thing, again, it was it was stated on the podcast, if I want to sleep, I close all the drawers. And I just I love that analogy because I use the analogy of tabs, of having a number of different tabs open. And I as I do my meditation sometimes, I think about my computer browser and having multiple different tabs open and just closing those tabs one by one such that I have a fresh, clean screen and I don't need to think or divert my attention to anything. And it it seems that we've been doing this throughout history. Basically, wherever we have a tool to store information or store things, we've used that as an analogy to try and calm down our brain and actually compartmentalise our brain in a good way where we can actually focus on one thing at a time. And I I just love that analogy. It's around 30 minutes into the Napoleon episode on how to take over the world and I'll I'll link to that in the newsletter this week. I just thought that was a wonderful analogy and it really stuck with me as well and inspired me to to talk to you guys about what my information diet is like. So let's talk about the nutrition podcast I listened to this week. So it was the Brain Health Revolution by the Sherzai team. The episode that I'm talking about is their second episode. It's it's called Science Under Attack, the battle between the past. And there's a couple of things that I I loved about this episode. A, the these guys talking amongst each other is it's very relaxing. It's listening to a conversation between two esteemed colleagues, two esteemed scientists who also happen to be husband and wife as well. And one thing that really stuck out to me is this concept of confirmation bias. So confirmation bias is essentially a bias that you have and you hold within yourself and you sometimes consciously, sometimes subconsciously are drawn to things that agree with your predisposition. We actually talked about this on the podcast that I did with them where I am drawn to studies that will qualify and promote the fact that I should be eating grilled fish because A, I love eating grilled fish. I I love eating fish. It's one of one of my my favourite meals. It's one of, you know, the best pleasures I have in life whenever I go away to European countries. I think about the food that I want to eat, you know, whether it be squid or muscles or razor clams, all these different things. Like that and and anything that confirms that, you know what, I should be eating fish and particularly oily fish and small. I I'm drawn to that. But the the thing they said about education, confirmation bias that I wanted to bring up is that education, so the the knowledge acquisition, the things that I'm doing like a masters in in nutritional medicine or reading papers every every week or or conversing with with other people, that doesn't remove your bias. Unless you're making a conscious decision to remove your bias, education alone doesn't remove your bias. It just gives you better language to confirm your previous bias. I I love that because that's essentially what I I honestly find myself doing and I'm being very honest and and making myself pretty vulnerable here, but I I think it's something that a lot of people do without consciously thinking about it. And actually, if I did want to remove my bias, I have to think about ways in which to to do that. And and and really what you want to be is a skeptic, not a cynic. A skeptic is is is someone who is willing to change their mind and willing to be coerced by the breadth of information, the reproducibility of of science. Whereas a cynic is someone who's essentially already made up their mind and will not be budged and will look for sources of information to confirm their viewpoint rather than be accepting of something that could be contrary to to their opinion. And and I think, you know, again, this comes back to the whole concept of your information diet. People have lost the ability to hold two conflicting ideas at the same time. You're either vegan or you're paleo, you're either red or you're blue, you're either conservative or you're labour. You you know, it's it's it's we live in a very polarizing time and I think we've always lived in a polarizing time, but the means by which we can get information and just how obvious it is to us is is been perpetuated by things like social media and and having information at our fingertips all the time. So, yeah, those are my thoughts on on on confirmation bias and nutrition and and those are where I get my information diet from. And I think for for you, if you're listening to this, don't worry about taking notes because I'm linking to all these things in the show notes, so you don't have to worry about that. So I should have said that at the start. But for you, maybe you should write down what your information diet is. You know, how many articles do you read? Where do you read them from? Have you tried different sources of information? Have you started listening to more right-wing sources of information rather than left-wing or center-left versus center-right? Obviously, something that's well written and, you know, not just pure propaganda, but start listening to people's viewpoints who are contrary to yours because it makes you a much more well-rounded individual and I and I think it it just ruffles the the feathers of your information that that might spark something in you as well. And I think that's kind of why I listen to things like history now and a whole bunch of other subjects because it there's a lot you can learn and there's there's there's a whole bunch of there's a wealth of information in different sources that that could be could be really beneficial to you. All right. So let's talk about some interesting articles. I probably won't have time to go through everything, but one of the things that stood out to me was the this microbiome driven approach to combating depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. Like I said, it's more of a review paper, editorial rather than primary research. But I do like reading reviews because they've done a lot of the hard work for you in that they reference they do a very good introduction. They do a reference point of what we know thus far about the microbiome, the population of microbes that live in and around our body, largely in our gut and the microbiome, the microbiome specifically refers to the genetic material of all those different microbes, which are largely bacteria, but also can contain things like fungi and viruses and nematodes. And what they they do is they they talk about the current state of affairs as it as it pertains to the surges in mental health illnesses, specifically those related to depressive disorders. And so they examine the the current literature surrounding the microbiome, the gut brain axis to talk about the advancements of potential complementary approaches. And it's it's great because what they talk about is something that's extremely promising. They use the vernacular like, you know, semblance of hope. So I think, you know, that this hopefully will galvanize a lot of scientists around this subject area because part of our understanding of depression has to lie in the gut. I've seen so much now, I've had so many people on the podcast talking about it now that it's more than probable and this is really where we should be directing a lot of our approaches. And what what they propose in this paper is that we should have a microbiome-based holistic approach that carefully annotates the microbiome or potentially annotates the microbiome through diet modification, through things like even probiotics, lifestyle changes, all these things that may address depression and the causes of depression alongside all the other interventions that we have as well, psychotherapies, medications, yes, and the wider determinants of whether someone is predisposed to depression, whether it be genetics or a combination of the genetics and their environment as well. Some of the stats I wanted to I don't want this to be another scary podcast. So I'm going to run through these pretty quickly, but some of the stats did did make me it was pretty worrying. So in in you're looking at US data, there was a 34% increase in prescriptions for anti-anxiety medications. And this is America. So we're talking huge numbers here, you know, population of 300 million or so. There was also an 18% increase in anti-depressant prescriptions and a 14% increase in common anti-insomnia drugs. So this is, you know, US, we already know that major depressive disorder affects over 350 million people. So that's bigger than that's basically more people than there are in America. That's how many people suffer with major depressive disorder. It's the leading cause of disability, something we've talked about before. But these, you know, these numbers alone are pretty stark. And I think if there is any intervention with a plausible mechanism that could alleviate, you know, even a fraction of their symptoms, then we should 100% be investigating it, particularly when it's cost effective as well. And when I say cost effective, I'm talking about something that we do two to three times a day. It's food. It's it's how we think. It's, you know, all these other elements. So we we really need to be taking this seriously because pharmaceuticals alone are definitely not doing the job. And the reason why I'm saying that, and I'm not just saying that off the cuff, is because we know that 30 to 40% of depressed patients do not respond to their first line antidepressant treatment and most, most, so more than 50%, don't have a satisfactory outcome on multiple medications. And that's before we get into the whole the whole issue around side effects and the fact that we don't actually have a complete understanding of the disease. I don't mean to humor this subject, but you know, it's it's pretty ridiculous that we don't actually understand that. And and and we haven't I don't again, like I don't want this to sound like a completely depressing subject, but it does have impacts on society as a whole. Treating these disorders is exceptionally difficult and it has impacts on physical health, increased unemployment, impaired social functioning, reduced productivity, obviously suicide. So, you know, very, very important topic. If there is any element that we could improve through through diet, given the wealth of other effects, then we should really be investigating it. So let's talk about the the gut brain axis. So your gut brain axis are, well, it's the bidirectional communication highway that between your your gut and your brain that occurs through neural, inflammatory and hormonal signaling pathways. So you've got your communities of bacteria and fungi that live in your gut and they directly and indirectly impact your brain and your emotions. It's something that we've known now for for a long time and there is a lot of evidence for the existence of this gut brain axis as well as the ability to influence it in a positive or negative way. So when you look at the gut in depression, you see clear changes to the gut microbiota in terms of their population and how different they look in in specifically in major depressive disorders. And that adversely affects many of the dimensions of the gut brain axis, including hyperactivation of something called the HPA axis, the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis. That is the connection between the hypothalamus and pituitary, which are parts of of the brain and how that influences your adrenal glands, which is primarily where you get the release of things like adrenaline or adrenaline. And you also get disruption of your neural circuits and your neurotransmitter levels as well. So neurotransmitters, things like dopamine, serotonin, all the things that we label as happy hormones, you know, it's it's kind of a yes, they are involved in the in the pleasure responses, but they they have a lot more of a role in terms of signaling as well and things that we don't fully understand. And you also, again, going back to the gut microbiota and the changes, you get excess production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the immune system. We've talked on a previous podcast with both Professor Felice Jacka and Drew Ramsey, the psychiatrist from from New York and Indiana, about the impact of inflammation, systemic inflammation on the brain and the likelihood of psychiatric issues. So when I say systemic inflammation, I'm talking about inflammation at a cellular level that exists around the body and that can be perpetuated by things like a leaky gut, also known as intestinal hyperpermeability, but also things like rheumatoid arthritis, injury, chronic autoimmune conditions with inflammation at its core. These can all disrupt the intestinal barrier, but they can also directly impact your the the brain as well that can lead to depression. We also know about the existence of the gut brain axis through established connections. So 40 to 60%, I'm reading from the paper now, 40 to 60% of anxious and depressed individuals report having an intestinal functional disturbance. So something like irritable bowel syndrome. We've always known that there is a correlation, but there is evidence to suggest causality here as well. The reason why we know that is because there are studies, although looking at animals in this case, where we transfer the poop from a human with depression, I know it sounds a bit icky, but it's called a fecal gut microbiota transplant or fecal microbial transplant. We transfer that into a rodent and that's been shown to induce a depression-like state in the animal itself. So, so there is the link between the potential causality of the microbes having this impact on the brain, although yes, it's in rodents, but it's, you know, it's something you probably can't, you wouldn't be able to, you wouldn't be able to get through that past. I mean, can you imagine an experiment where you put a depressed patient's poop into a euthymic, otherwise known as a level emotional state, someone who doesn't suffer depression and and give them the poop and then, you know, it just wouldn't it wouldn't happen. So that's why, you know, rodent studies are quite important in that respect. So moving more towards the solutions, okay, we we establish a connection, we know about the gut brain axis, we know about the impact of depression, we know how much of an issue depression is on a global scale. What are the potential solutions that these guys talk about? Well, I think the first thing to acknowledge is the fact that rebalancing the gut microbiome in individuals with major depressive disorder could be a promising step towards assisting those individuals. So the first thing they talk about is obviously diet. So if you if you think back to COVID, and I'm going to use myself and put myself again in a vulnerable scenario here, where during the hard lockdowns, what what were you, what were you eating? And I know for me, because I essentially went full time at the hospital, so my my patterns were all disrupted. I was feeling obviously quite low, anxious. What did I do? I I ate loads of unhealthy food, you know, I I was obviously eating a lot of the sweets that these kind-hearted people had sent to the hospital. You know, there was chocolate everywhere. I wanted to eat comfort food. So, you know, we'd be ordering loads of stuff, like takeaways and all that kind of stuff. I definitely increased my alcohol consumption, not to detrimental amounts, but certainly, you know, I I'm someone that doesn't really drink at all if I'm honest. I'm quite boring like that now. But I was definitely having at least one one to two glasses of of wine a day, which is completely out of the ordinary for me. And we know that unhealthy foods disrupt the microbiome. Alcohol, again, we know can create intestinal hyperpermeability, also known as leaky gut. These all have an impact. I'm not saying that this alone was the reason why people why we saw an increase in depressive outbreaks during the the pandemic, but it certainly didn't help and it certainly may have added to the likelihood of people suffering a depressive disorder, particularly if they have a predisposition to depression genetically or they have an environment that is psychogenic, as I described, so something that can can push someone towards that. The guys, and I'm not alone. So the the guys who who did the review refer to a a UK study in which 2,000 adults were were given a questionnaire and they found that 80% of people reported an increase in unhealthy options. So I'm not alone. I'm four and five. I I wasn't the one in five. I definitely increased my unhealthy options. To be fair, like I probably ate better I still ate very well, but you know, I just increased my unhealthy options massively for me. And there was also a 36% increase in alcohol consumption as well. So these dietary impacts can have an impact on depressive symptoms as we know. We don't know the exact underlying mechanisms, but some that have been proposed could be related to oxidative stress. So oxidative stress is the imbalance of your reactive oxygen species versus the antioxidant impact of of diet as well as some of the other cells that you have innately in you as well. Inflammation, as I've already discussed, and mitochondrial dysfunction. So mitochondria are always sort of described as like the powerhouses of your cells. You know, they they generate ATP. They have distinct DNA from us. So they're actually a remnant of of bacteria. It's it's it's actually very it's it's a quite a complicated structure and something that I probably don't fully understand myself. But the other the other roles of mitochondria are in signaling as well. So it's not just they're not just powerhouses of energy, but certainly the dysfunction of mitochondria tends is something that we tend to see in people with mental health disorders as well. So there are a whole bunch of of elements here where the disruption of healthy eating patterns and increase in alcohol could have had an impact on the likelihood of depressive depressive episodes. Obviously, a good diet tends to have vegetables, fibre, vitamins, minerals, all these things that are packed with polyphenols, the good bioactives that I always talk about on the podcast. And these nutritional factors are associated with decreased depression rates, you know, potentially because of their modulatory role on inflammation, potentially because of the bioactives and how they are neuroprotective, and also, as we'll talk about in a bit more, their prebiotic properties. So just a little refresher, prebiotics, things like garlic, onion, chicory, are specific types of fibres that modulate the microbiota in a positive manner. So they are specialized fibres that are uniquely positioned to grow and provide lots of substrate or food for your microbes so they can slave away for us seven days a week, every hour, every minute. They don't ask for anything in return. All they want is good food and that's what prebiotics specifically are very good at giving them. The the paper then turns to probiotics. So we've talked about diet, we've talked about the potential negative impacts of a poor diet, the potential positive impacts of a good diet. Probiotics. So again, refresher, these are live microorganisms which when administered in adequate amounts, and I think that's very, very important here, the adequate amount, confer health benefits to the host. And the way that that this is proposed in terms of how this happens is because when you introduce these different probiotics, they modulate the population in such a way that is beneficial. So they might provide diversity to the population. Some of them might be really good fermenters and they create, you know, these wonderful short chain fatty acids that nourish the gut cells or are involved in neurotransmitter production, which improves the balance of the neurotransmitters that are being produced. Some microbes that are introduced by probiotics prevent the adherence of pathogenic microbes. So pathogenic being those that are detrimental for the gut. So again, they're all serves to create a much more harmonious environment in your gut, which allows it to do its job and and can reduce the likelihood of inflammation, all the other things that can can lead to a whole host of things, but in this case, we're specifically talking about depressive symptoms. And so probiotics could serve this critical function of keeping the microbiome in balance. And they refer to again, animal and human studies that show a reduction in anxiety and depression comparable to medications when being administered probiotics. Now, I I just want to state here that the the evidence for this is mixed. So there are some studies that show a beneficial um a beneficial impact of probiotics on on the gut and and on specifically anxiety and low mood symptoms. There are some that don't show anything at all. They they basically show negative results. But we also have to consider the unpublished studies. And the unpublished studies are usually the ones that are negative because most journals, and I'm not, you know, saying anything against journal editors, you have a hard job, lots of research, particularly on the microbiota being produced. But a lot of negative papers, i.e. things that don't really show anything, tend to not be published because they're not sexy. You know, if you think about it from the perspective of what drives sales or clicks or whatever, it it's just as rife in the scientific literature. So I'm more likely to click and and very honestly, I'm more likely to click on a paper that shows probiotics reduce the incidence of depression by 30%, yada yada yada, versus probiotics administered over two years with, you know, this selection of microbes used in the formulation have zero effect. You know, I'm like, oh, okay, fine. It's not it's again, it's my confirmation bias as well. It definitely comes into play here. I'm more likely to want to click on something that I want to believe. I want to believe in probiotics, but I think we have to be very pragmatic about this as well. So they definitely show promising role, but we don't know exactly how promising, what's promising, and what the mechanism is specifically either. I reckon there could be a whole host of reasons as to why probiotics may or may not work. The interesting thing, I think, that was stated in this paper is that probiotic therapies may produce certain benefits over therapeutic drugs. So there have been some studies where they gave probiotics and they found a better benefit than antidepressants. Or play an adjunctive role. And I'm more interested in the latter because I I think rather than trying to pit two things against each other, when they play such a different, when the mechanism is so different, I I think it's more likely to be complementary rather than anything else. Um, that, you know, a lot of people have stated that, um, particularly the the drugs that we use in psychiatric disorders, specifically depression, serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and a whole bunch of others, you know, whether they're being potentiated in the gut, that's very interesting because if you have a complementary supplement in a multi-strain probiotic helping the pharmaceutical do its job, I I think that's that's a really interesting and I haven't I haven't come across a study yet that looks at the combination of them in the same way, you know, immunotherapy might be, immunotherapy for cancer might be benefited by a better diet or even probiotics themselves as well. I think I think there's an interesting research study for for that. Um, but I haven't come across it yet. All right, so let's let's talk about the other lifestyle elements of this paper. I think I'm just going to end up talking about this paper now because this is going on for ages. Okay, so exercise. So again, during the pandemic, decline in all types of physical exercise. Obviously, exercise plays an important role in a whole bunch of conditions, cardiovascular disease, and it also has an important role in increasing the diversity of the gut microbiota and maintaining the balance between your beneficial and pathogenic bacterial communities. So if we're going to be reducing the amount of exercise that we do, it's obviously going to have another hit on the microbiota. So you can just see these marginal hits on the microbiota, alcohol, unhealthy diet, your environment, your lack of exercise, all these different things conspire to hurt your microbiota and your microbial community. So the potential mechanisms of why exercise has this effect, this beneficial effect is that it increases the availability of your brain neurotransmitters like dopamine, you know, your feel good endorphins. So that's the endorphin sort of hypothesis. Um, you've also got something called the monoamine hypothesis. And this is where following exercise, you have an increase of norepinephrine and serotonin that we've actually observed in plasma and urine following and and and various brain regions as well, following exercise. So that's called the monoamine hypothesis. It basically boosts all these different neurotransmitters that have positive effects on your on your brain regions. You also have exercise alleviating depression through those neuro molecular mechanisms. So that's increased expression of neurotrophic factors. We've talked about this on the pod in the past, the BDNF or brain derived neurotrophic factor and regulation of the again, the HPA axis activity as well, increasing the availability of your endorphins and reducing your systemic inflammatory signaling. So exercise basically is like one of the things that we we should all really be doing every day. I mean, I do I do it every day. I can't start my day without doing some form of exercise, even if it is just stretching. Um, you know, that has been shown to improve stability, um, core exercises, all these things. It doesn't always have to be a jog. You don't always have to, you know, go outside. You can do it from the comfort of your own home. If you can get outside, brilliant, you'll get the dose of of of morning light as well that will adjust your circadian rhythm. So, you know, this is basically everything I'm talking about is basically conspiring to that simple way of life that is very simple and the solutions are very simple. The implementation of it and the execution of it is is the hard thing. So I'm not shying away from that. I think obviously that is is very hard to do. Um, but I'm just going to give you the facts and and hopefully the podcast and the stuff I put on social media and the books can can help you to execute these and implement these on a daily basis. Another interesting point I want to make about the exercise impact on the brain is that it the most obvious thing is that it increases cerebral vasculature. So that's the vascular connections between all the different areas of your brain. You're introducing a lot more oxygen to those areas. You're driving capillaries to grow. You're you're preserving your your brain integrity by making sure that you're giving a good dose of blood flow going to your brain as well. So that will contribute to the development of new neurons and the synaptic connections between your neurons. So you're essentially creating neuroplasticity, synaptic connections and boosting cognitive function. So again, lots of reasons why we should be exercising. It's just the implementation of doing it every single day and and putting it into practice. So the conclusion, I just I've spent way too long on this. So the conclusion of of this review paper is that depression has been shown to be linked to a disruption of your microbial populations in your gut, something called dysbiosis in the microbiome. And knowing what we know now, we can make lifestyle habits work for us instead of against us. And this is the crux of everything, you know, if we know that a healthy diet full of polyphenols, bioactives, all those anti-inflammatory chemicals, prebiotics can serve us. Okay, that's the solution. The hard bit is how do we allow people to eat this way every single day? How do we create environments and communities where this is the norm? How do we create a culture around healthy eating that we don't have to necessarily opt into, we have to opt out of. Right now, we our default is takeaways, it's junk food, it's quick, it's croissants, it's refined carbohydrates, it's when you go to a coffee store, you know, it might look healthy, but it's actually full of refined sugars unfortunately. So all these different things they conspire against us and that's why healthy living in this day and age is it's a lot harder than it should be. And again, you know, it's just creating this environment that allows it. And I know it's an extreme example and an extreme what I don't actually think it's that extreme. It's it's like smoking. We had to we had to endure decades of research to demonstrate the negative impact of smoking for one. But then, even though we had clear, clear understanding of how detrimental smoking was, it took another few decades for us to remove advertising, another few decades for us to remove it from public spaces. And those would have been seen as extreme, you know, something that we all do, something that we have a right to do, something we can opt into and all these different things. So, you know, when you when you actually look at everything in totality, I'm not just looking at this review paper, I'm looking at it through the perspective of Alzheimer's, of cardiovascular disease, of obesity, you know, all these things, it's it's having a huge, huge impact. So we have to get quite serious about this. So yeah, so those are those are the the essential conclusions. Lifestyle, the microbiota driven approach, why the pandemic has uniquely positioned us to make us more depressed and what the potential solutions are that are within our remit of control, but also things that we probably have to legislate for as well. That was a long discussion. I'm going to try and make that a lot shorter next time, but hopefully you found some some information there that was interesting. So this study was was in PLOS One and it's called biomarkers of dairy fat intake, incidence of cardiovascular disease and all cause mortality, a cohort study, systematic review and meta analysis. Sounds amazing, right? So basically, this caused like a whole bunch of stir around the headlines last week. So I want to and I was going to talk about it on morning live, but it got cut for some reason. So anyway, I thought I thought I'd use the research that I've done for this for the podcast. So, um, this basically looked at biomarkers of dairy fat intake. And the biomarker they use is something called serum pentadecanoic acid, 150. This is basically looking at a particular carbon chain length of of fats. They also looked at another one called trans palmitoleic acid. It's it's basically another carbon chain length. And it's what we use as a proxy for dairy fat in the blood. And what they did is they at day zero, they measured these biomarkers at baseline in in about 4,000 Swedish adults. And it was it was well adjusted. They had a nice mix of of age and and male to female ratio. And they basically followed them up for 16 years. And what they found after 16 years was the higher the amount of dairy fat in the blood as measured at day zero by pentadecanoic acid, the 150, that was associated with a lower incidence of cardiovascular disease and lower all cause mortality as well. Sounds great, right? So it seems that more dairy fat in the blood was associated with lower cardiovascular disease after 16 years. Now, they don't repeat the biomarker at 16 years. They just look at the incidence of cardiovascular disease and all cause mortality. And I think that that's the the biggest limitation of of the study in that you don't know whether that dairy fat level was consistent over 16 years of follow up because they they only assess those biomarkers at day zero. They didn't do it at day whatever 16 years in the future is. And so, you know, that's a huge limitation of of the study. And also, it's impossible to distinguish the types of dairy foods that correlated with the high levels of dairy fat biomarker as measured in the in the blood. So, you know, these are big things. But to the author's credit, they're not trying to make the assumption that you need to eat more dairy fat in your in your diet to reduce your incidence of cardiovascular disease. That is the exact opposite of what they're saying. What they also did is do something called a meta analysis, which is they basically where they bundle up a whole bunch of studies, including their study, and they also found similar things. So they found this association between high levels of the biomarkers in the blood and and lower cardiovascular disease. So what they say is this is interesting. It goes against what we would think, but what it does, what this piece of research suggests is that we need to do clinical and experimental studies to elucidate the causality of this relationship and the relevant mechanisms behind it. So what we're saying is this is an association. It has no bearing on on whether this is actually true or not, but we should definitely look into this because it goes against what we're currently advising. They even go as far as to say that other fats, like those found in seafood and nuts and and extra virgin olive oil and and stuff like that, have greater health benefits than dairy fats as well. They they also say that. But as you can imagine, I'm just going to read you a title from a newspaper. Eating more dairy fat linked to lower risk of heart disease. Now, that's true. That is that is there is a link there. They're not saying that it causes it. They're not saying that that's actually okay. Obviously, it's written in a way to grab your attention, talk about the French paradox and all that all that stuff and you know, everyone wants to eat the cheese and who doesn't want to eat cheese? I want to eat cheese. So, you know, you can understand that. But the the very next paragraph, I have a big issue with. Researchers have found that cheese and cream may indeed ward off heart problems. That's incorrect. That's not that's not what the researchers have found. They found a link and it needs to be further investigated. But that's definitely not what they found. So that's actually factually incorrect. And that was from a broadsheet paper. I don't want to I don't want to get sued, so I'm not going to I'm not going to name who it was, but that's from a broadsheet and you'd expect a lot better from said broadsheet. I can't imagine what the other papers would say. I'm sure it'd be, you know, written in a completely bastardized way from from what the authors would have wanted. So it's just something to be aware of that A, we're talking about observational studies here, the lowest form of the lowest quality in terms of the hierarchy of studies, the lowest quality of study. So we can't really glean much from it. This is the big, big problem with nutritional science in general, which is why I I honestly have a love-hate relationship with it. Within this study itself, you know, it's it's impossible to figure out the quality of the dairy foods that certain people might be consuming. It's only done in Sweden with Swedish adults where they have quite a high consumption of dairy. So their microbiota, something we've been talking about already, might be better suited and adjusted to having that much dairy compared to someone from, I don't know, India or Sri Lankan origin or wherever. You know, so so again, the personalization element is definitely not there, particularly in observational studies. The health impact of dairy foods might be dependent on the type as well. Is it an aged cheese? Is it a yogurt? Is it milk? Is it kefir? Is it fermented? Is it butter? You know, all these different things. And also, let's let's not forget that the your risk of disease is not down to the inclusion of one ingredient alone. Your overall diet quality is super important. That is the most, most important thing. And when it comes to anything, whether it be a traditionally healthy ingredient, whether it be broccoli, or whether it be something like, you know, bread, it comes down to the two things I always talk about, quantity and quality. How much of the said ingredient are you consuming? What is the quality of the ingredient that you're consuming? With bread, you know, how much of the bread are you having? And you know, are you using a whole grain bread? Has it got loads of nuts and seeds in it? Is it been allowed to ferment properly? Is it sourdough? Is it a prebiotic? You know, there's so many different types of of each ingredient. So quantity and quality are the are the two big things I always talk to people about. And just another sidebar on cheese, you know, it is a good source of vitamin K. It has probiotics. You know, if you're getting an aged cheese, you're getting a very good quality cheese. If it's raw, unpasteurized, you're going to get some of those bacterial elements as well. So there there might be some some some other benefits that we we don't fully understand from aged cheeses. But again, you know, I mean, I personally can't eat that much dairy products because it gives me a funny tummy. And a lot of people have that issue as well. And and that's going to cause gut inflammation. So, you know, everything has to be taken with a pinch of salt and just because one study says something about positive about dairy doesn't mean that for you as an individual, it's going to be beneficial. You really have to personalize this stuff yourself. And and hopefully, you know, I can give you some sort of advice that is actionable and something that you can take towards your to your kitchens and your family and actually start putting into practice. So, so yeah, those are my those are my thoughts on on that particular study. And I just think if you just remind yourself of the discrepancies behind how the media put stuff out there and and the issues within nutritional science itself, just take everything with a pinch of salt. That's what I say. Cool. All right. I don't think I'm going to have time to go through the other things because I've been wittering on for for way too long here. If you know, if people like this kind of thing, what I can do is a shorten it because I think I've been talking way too long here. Um, I can pull out different studies and stuff and we can talk about some some interesting stuff. If if you like that, I won't go too hard on the science stuff because I think that can get a bit boring and I'll stick to the takeaways. So the takeaways for for this week are that, you know, check out what your information diet is. You know, where are you getting your information from? Are you listening to angry sources of information? Is it all negative? Is it news? What books are you reading? Is it is that a nice mix of different elements? I I catch myself quite often, you know, just just doing two topics of interest for me like nutrition or tech or or that kind of stuff. I need to mix it up and that's why I started listening to a history podcast and trying to learn a bit more about meditation, for example. It's all kind of the same thing in terms of what my core interests are, but I think that's that's certainly something a good takeaway for for anyone listening to this. We talked about the gut brain axis. It's real. It definitely has an impact on the on mood states. Enhancing the microbiota alongside other factors like psychology and even pharmaceuticals to to some degree could be pragmatic decisions. I'm super excited about that and I think we can do things today that can protect our mental our mental wellbeing and our and our prevent depression in the future. We talked a bit about dairy fat and and how yes, there is a study that links dairy fat with with potential cardiovascular protection, but that doesn't mean that it's caused by that. There could be a whole bunch of other elements in the diet. It's an observational study. There are so many issues with those. So, yeah, hopefully you find that useful. And if there's one thing I want to leave you with is this idea of Napoleon, one of the most successful conquerors of our time, someone who was a foreign refugee who went on to take over France and create a huge empire. And his what might have been key to him is the ability to compartmentalize his thinking. I've been talking too long. And the ability to to put things in drawers, shut one drawer, open another, and then shut them all when he needs to rest. And I think I I definitely need to do that right now. Thanks so much for listening. If you want to leave us a review, please do leave us a five star review on Apple or wherever you're listening. And also, if you want to give any feedback and it's negative, then just send me a message rather than putting on my ratings because that that won't be that won't be very good for the podcast. So just just join the newsletter, there's a feedback thing there. Shoot me a message. I read all of them. I can't reply to all of them. I will try and reply to as many as I can. And so just shoot me a message there and thank you so much for your attention. I really value it and I hope this podcast will continue to inspire and give you information and help you lead healthy, happy lives. Take care.