Dr Nick Fuller: Inevitably, your body claws back to the start point. So this is why we typically see a U-shape or V-shape response with weight loss programs, dieting programs. Your body's going into this shutdown mode. And as you mentioned, there are eight well-researched biological pathways. And this is just one of them. This is just one of these clever wiring systems, physiological responses that's taking place within the body when you lose weight. So basically, what I'm saying is, sadly, and what the dieting industry won't tell you, is that you are doomed for failure the minute you start this diet, because your metabolism or your metabolic rate is going to lower. And it's going to lower in order to climb back to its start point, because that's what it thinks is needed in order to survive.

Dr Rupy: Welcome to the Doctor's Kitchen podcast. The show about food, lifestyle, medicine, and how to improve your health today. I'm Dr Rupy, your host. I'm a medical doctor, I study nutrition, and I'm a firm believer in the power of food and lifestyle as medicine. Join me and my expert guests where we discuss the multiple determinants of what allows you to lead your best life.

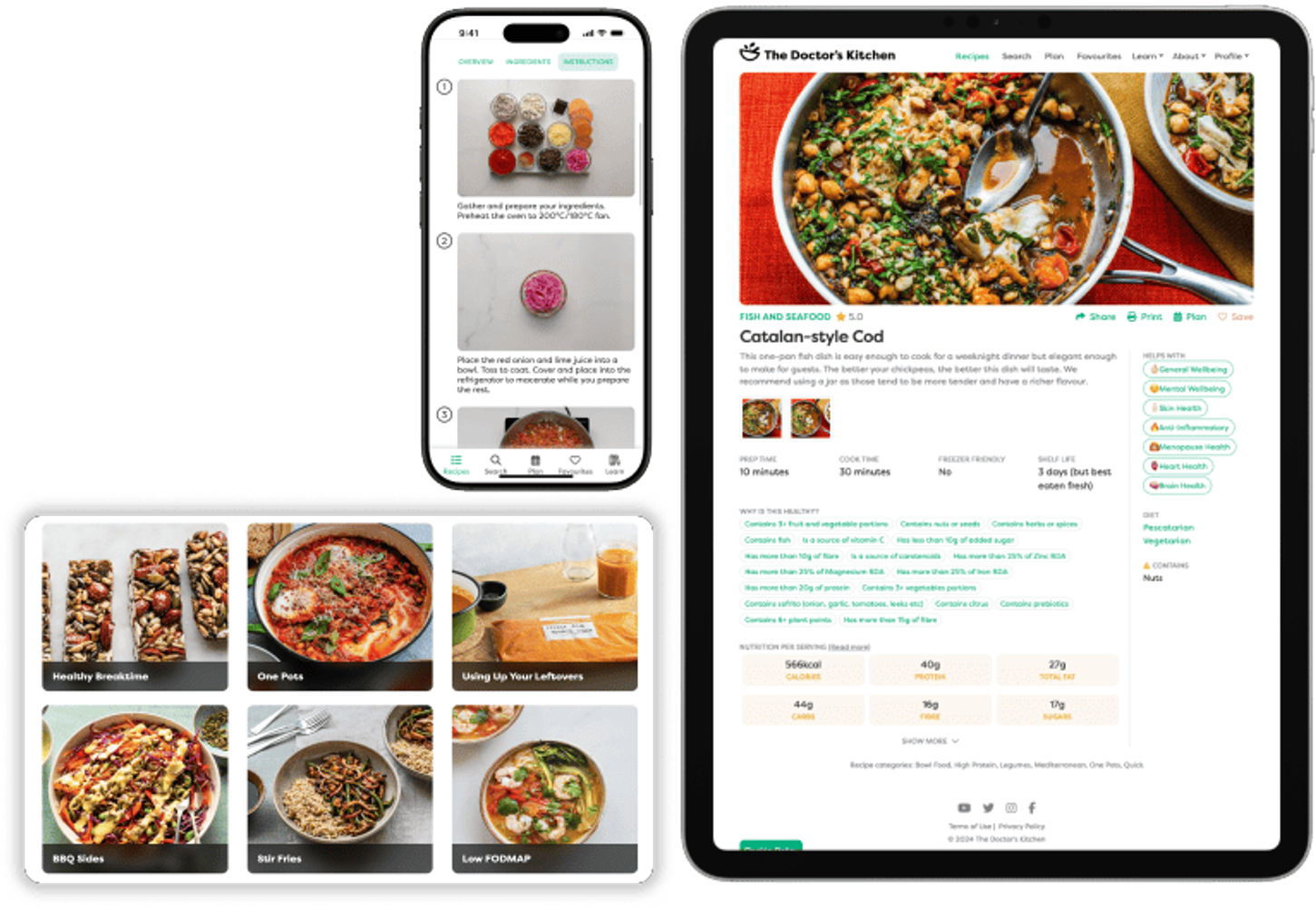

Dr Rupy: Today on the podcast, I have the pleasure of chatting to Dr Nick Fuller, a leading obesity researcher in Australia with over a decade of experience. And he brings together a diverse set of skills, having held positions in both the industry and academic sectors. His current position is commercial and industry program leader within the Charles Perkins Centre at the University of Sydney and involves working with government and industry to identify and develop cost-effective treatments for obesity and related physical and mental health disorders. I really like Nick's work because it's resulted in policy change in the field of obesity and metabolic disease. Plus, his research has been published in two of the top three ranked medical journals, The Lancet and JAMA, with huge impact factors as well. The interval weight loss program, which is something we get into a little bit later, was selected for the prestigious Incubate program at the University of Sydney and was awarded the University of Sydney's Genesis Prize and received multiple awards for its research impact in the general population. We have a very pragmatic conversation about compassionate weight loss and how better understanding of the biological mechanisms behind obesity will help you, the listener, and the countless millions of other people across the world better understand why it's not willpower that is resulting in lots of people failing on their weight loss journey. It is actually how our bodies are designed. We talk about the homeostatic regulation of body weight as occurring centrally in the brain as well as peripherally. We go into briefly about the anorexigenic and orexigenic hormones that are released from the brain and from fat tissues as well as other organs. The influence of hedonic hormones, so your dopamine stores and actually some of Nick's research involves looking at functional MRIs and looking at the release of these addictive hormones and why food addiction is a real thing. We also talk about how weight loss actually brings about changes to energy stories, storage, and how your body partitions fuel. We talk about the responsiveness to food reward with decreased control of food intake that's basically the impairment of your body's ability to sense a positive energy balance following weight loss. What this basically means is when you lose weight, you lose the marker to actually determine how satiated you are because your body is going into starvation mode and it will overeat. And that's what leads to this classical U-shaped curve of weight loss, weight regain, and over-regain as well. I really did like this conversation, which is it's super empathic. It's clear that Dr Nick has got a lot of understanding of both the physiological mechanisms behind obesity, but the knock-on effects on psychological well-being as well. And the interval weight loss program sounds like a very sensible and sustainable weight loss program that is embedded in science and the years of research that himself and the team have put into this as well. I really do hope you enjoy listening to this and like I said again, these series of podcasts are conducted with as much compassion and empathy as possible, but I do think we need to give people the tools to understand how our bodies work such that they can achieve weight loss if appropriate and lead healthier and happier lives. I'll leave it as that. Please do check out the show notes on thedoctorskitchen.com. You'll find out a lot more about the research plus some of the academic studies that we've discussed on the podcast today in a bit more detail there. And I hope you enjoy this chat.

Dr Rupy: Nick, thank you so much for being on the podcast. Uh, mate, it's a pleasure to have you here.

Dr Nick Fuller: It's great to be on, Dr Rupy. Greetings from the land down under. Also one of your own homelands, so looking forward to catching up when you come back to Australia.

Dr Rupy: I know, I know. I miss it, you know. We were just talking about how I'm an early riser over here in the UK and I'm seeing like a bit of an outsider, but in Sydney, the coffee houses are packed by like 6:00 in the morning. Everyone's coming back or going out to a workout. It's, it's such a lovely atmosphere.

Dr Nick Fuller: Yeah, it's a lot different. It's, everyone's certainly got the coffee fix very early, probably three or four cuppas by the time of nine, by the time nine hits. So, uh, yeah, it's, it's, I guess it's a big part of our culture of getting outdoors, particularly where I'm lucky enough to live close to the beaches. But yeah, we will be catching up when you're back.

Dr Rupy: Definitely, definitely, mate. Well, let's, obviously we're going to be talking about the mechanisms behind body weight regulation and the kind of work you're doing helping patients achieve sustainable weight loss. But I'm, I'm fascinated to know a bit more about how you got into this field yourself.

Dr Nick Fuller: Yeah, absolutely. So I guess to put it into context, I work at the University of Sydney and Royal Prince Alfred Hospital. Uh, we have a facility called Charles Perkins Centre, named after Charlie Perkins. Uh, and basically, we are running Australia's largest obesity or weight management service. And what I mean by that is, we're seeing the largest volume of patients every year, both in our hospital clinics, but also in our research programs. So, uh, with the research programs, we're, we're, you know, working with government and industry, um, trialling and testing different products, lifestyle programs, devices, drugs, surgery, uh, to paint a better picture of what weight management should look like to help people, um, you know, that are struggling with their weight. Because when we look at the stats, we all know, um, how, how bad it actually is and that this obesity epidemic is not going away. Um, if anything, the trend is, is, is going up. The number of people that are struggling with their weight in Australia, um, and also, you know, a lot of these other countries like, um, England or the UK, US, uh, are seeing roughly two in three people with a little bit of extra weight around sort of that mid-drift waistline. It's a quite, you know, scary statistic. And what that means is, um, when you carry the extra, extra weight, you're going to be at increased risk of other metabolic disorders or diseases like type two diabetes, heart disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, heart disease, for example. So, yeah, my work is, um, you know, as a clinical or clinician, um, and researcher, helping people on their weight loss journey and importantly, um, which I hope we can educate a lot of listeners through today's chat, uh, around the diet, well, I guess dangers of dieting and why some of these programs and diets that we're following are actually doing more harm than good. Uh, before working in this clinical environment, I was actually in a corporate sector and giving the advice to a lot of these people that we put through, uh, these weight loss shows. It was something that, you know, at the time I was not, um, particularly proud of. I knew what we were doing was for visual effects and that these people were going to be worse off long term, which then drove me back into an academic and clinical setting so I could actually research what's happening within a person's body when they're losing weight because sure enough, they're out there losing weight. That's the easy part, but the, the nature or the fact is that they're actually regaining that weight and they're ending up stacking on more weight than, than they lost. And, um, it's, it's much more complicated than people think. Obesity is a science and there's a lot of education, um, that is needed in this space so that people can be, uh, empowered to regain control of their health and weight.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, definitely. And you know, I appreciate the honesty as well about how your advice has changed over the years and I think we're all sort of guilty of, um, perhaps giving or having, uh, certain ideas about weight and how easy it is to lose weight if you just have that motivation, um, throughout the number of years and it's great that we can all educate ourselves on this. Just to give us a scale of the obesity issue in Australia, um, what does that look like across the country? Because you guys have got a smaller population than the UK, but across a landmass that's similar to, uh, America.

Dr Nick Fuller: Yeah, absolutely. We do have a very small population. Um, mid-20 million. Uh, but when you, you look at the sort of leading countries in terms of, uh, prevalence of overweight and obesity, ours is, is, yeah, a daunting sort of 67% or two in three people that are struggling. We're seeing that prevalence higher in lower socioeconomic groups, um, throughout the country. But, yeah, what is really also of great worry is that more of the people that had overweight or clinically diagnosed as overweight are now in that obesity range. So they're moving along that spectrum. And the other scary thing is that a lot of people are actually dieting themselves into an overweight range. So they start off at this, maybe the upper end of what we clinically diagnose as, as, as normal, um, weight range by BMI, body mass index. And then that societal pressure, um, to conform to body images that really aren't healthy and normal, pushes them into that dieting industry and they go through this never-ending cycle and actually drive up their set point or their weight over time. And look, a lot of the measures that we've got in place aren't actually helping. There's a lot more that needs to be done, not only here, but across the globe.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, you know, I think those statistics are really going to be, um, shocking for a lot of people in the UK because I think over here we have this idea of the Australians being, you know, fit and healthy and going outside on the beach and stuff. And I remember that was certainly my impression when I first came to the country seven years ago. And I was shocked at the statistics back then and it feels like it might be creeping upwards as well. And the other point about how when you're perhaps at the upper end of the spectrum in terms of weight and then you go into a dieting sort of, um, culture or, you know, program with good intentions and then you actually end up putting on more weight and and getting to a cycle where you can't lose that weight. I mean, that that's pretty scary. And I'm glad we're we are talking about that. Um, let's, let's go into how we actually regulate weight, um, in our bodies because this is quite a complicated process. You shared a few papers with me that I'm going to put on the show notes as well. Um, but, but perhaps we could go through exactly what drives obesity.

Dr Nick Fuller: Yeah, I guess, um, you know, if we think about that prevalence of overweight and obesity, uh, before the 1970s, most of the population were in a healthy weight range. Um, now when we walk around and in Australia, two in three, you know, have that weight problem. So you wind back the clock a few decades, uh, before the 1970s. And a very clever part of the brain called the hypothalamus was very good at regulating our body weight. We get signals sent from our stomach, um, and our gastrointestinal track, acting on our brain telling us when and when we shouldn't eat. Now, that worked perfectly fine, but then during the 1970s, 1980s, that's when we did see this evolution into what is now the modern day environment or obesogenic environment. Uh, food or fast food, processed food is on every corner of every block. We use motor vehicles to get everywhere from A to B. We use devices and technology all day and all night, which keeps us awake at night. So, really, what has happened is, um, yeah, we've seen this, this, I guess, a boom of the modern day obesogenic environment and evolution of that environment. Um, so now the homeostatic regulation of our body weight is not actually working because what happens is the hedonic or reward pathway overrides it. So you walk down, uh, the street and you see your favorite bakery or fast food restaurant, and your brain lights up, you get dopamine released, which is the learning chemical, telling you to go back to get more of it because last time you ate it, it made you feel good, at least at the time you ate it, maybe not afterwards. And that's the reason why when you sit down at the dinner table, you can always say yes to the dessert. It's the hedonic or reward pathway kicking in saying, yes, I can fit that in even though your energy stores are full. So remember, these foods weren't in existence like they are today and as a result, we kept within a normal healthy weight range, that homeostatic regulation of our body weight worked. Now, the 1970s, 1980s, environment changes, hedonic pathways creeping in, we have a hard time saying no to our favorite foods, even though our energy stores are full. And then in combination with that, we're not moving, we're not getting good sleep, and it results in poor lifestyle changes. So consequently, since that time period, we've seen a rough 0.5 to one kilo increase in our weight every year. And over the course of 10 years, you know, that can quickly result in the five or 10 kilo increase. It could be due to a change in your career, taking on a new job, starting a family, whatever it might be. And then what do you do? And particularly women, you react by dieting. You sign up to the latest and greatest diet, which has been, you know, self-validated by a social media sensation or a big name celebrity pushing it onto their followers, and you follow it. Um, but as we'll get into, it's, it's actually, um, very hard to succeed on your long-term journey. And that's because there are other factors, um, that kick into gear and take, I guess, yeah, have, have a much bigger contributor to, uh, what is going on long term. So, yeah, I guess, you know, we've evolved to this point now where weight has increased, it's got out of control, we can't say no to our favorite foods. We continually react by dieting. We do it up to five times every year. So there's certain polls and the UK are very good at doing this, these dieting polls, but people are doing anywhere between sort of two and five diets every year, about 60 diets by the age of 45, and spending about 30 years of their life dieting. So in summary, most of these diets are actually contributing to the problem they proclaim to solve. And that means that it's accelerating your weight gain. Um, and there is actually another great paper, uh, which I can send through to you, but it looks at twin, a large data set of twins, uh, 4,000 in total. And basically they followed them up over 25 years. And they showed that the twin that had been dieting or intentionally losing weight over their lifetime was always heavier than the one that hadn't. So independent of genetic factors, weight was actually driving up their weight over time.

Dr Rupy: Wow, wow. And we, we can definitely get into that, um, when we talk about the impact of weight. But you know, I think you've laid out the picture there really well because evolutionarily, we are geared to protect against weight loss more than weight gain. And I think when you eloquently describe that change in our modern environment, it's no wonder that we are putting on weight as a population. And, you know, I am definitely in that camp where I struggle to say no to dessert. Like we have a running joke actually with me and my sister about how we'll go out for a family meal whenever that was years ago now. Um, and there's always space for dessert, even though we're absolutely stuffed. Um, and I have to really struggle to say no, but you know, I usually end up having it. Um, and the hedonic, you know, it's that hedonic influence. You know, when it comes to dopamine, um, and those reward pathways, um, uh, what, what actually goes on in our brain? Because we've got functional MRIs now, so we can actually see what lights up when people, when people eat. What, what impact is that having on people who perhaps don't fit into that overweight category versus those who do?

Dr Nick Fuller: Yeah, this is another fascinating part of, of research we do as well. You can measure brain activity, as you said, um, and, you know, in, uh, patients, participants that are coming through our clinics, in essence, they're really guinea pigs. Sure, they're getting state-of-the-art care, uh, healthcare, but we're also analyzing and, and probing them and getting all sorts of samples of them off them as they go along their journey. So that might be measuring the metabolism, it might be taking bloods to see what's happening to their appetite hormones, but it could also be measuring their brain activity. So, uh, someone that's in the normal healthy weight range, remember, very few people actually tick that box sadly these days. Um, they're typically seeking out lower fat foods, uh, lower sugar foods. But when someone does develop, um, a weight issue or clinically diagnosed as overweight or having obesity, you'd see a preference, um, to more high fat foods. Now, the other worrying thing is that as they lose weight, you see a preference towards high fat and high sugar foods so that they go and seek out all these high calorie, nutrient dense foods, which add more energy, which helps you stack the weight back on. Um, but yes, you do see a change in brain activity. You see, um, this heightened response in that reward pathway. So you go and reach for more of those foods because like you said, it's in order to protect your set point. Our body is so good at protecting against weight loss. Unfortunately, it's not as good as protecting at protecting against weight gain. It still does a pretty remarkable job. I mean, if you think about it, day-to-day, we don't eat the same foods. One day you might go and gorge and have a pizza and have a few beers or whatever it might be. The next day you're eating your salads and your greens. But really, your weight is, you know, it's fluctuating based predominantly on, on, um, variation in water, body body water content. But it's staying at that set point. And, you know, for, for you, Dr Rupy, it could be in the 100, for me, it could be the 120, for Paul, it could be 100, uh, 90 and and Paul down the road 60. But that's that weight you will always protect. And that's the weight that we're sort of evolved, um, to defend. So, unfortunately, it does a very good job at protecting, um, itself. And when you lose weight, this is what's really going on. It's this evolutionary desire or evolutionary propensity to actually regain the weight you lost. And it's in order to survive. It's in order to procreate because during our time as ancestors, and we're hunter gathering for food, it wasn't always available. We would go very long periods without it. When it was available, we would then gorge. We would seek out those high sugar, high fat foods, and we would store it. And then when food wasn't available, our body was very good at shutting down so we could hold on to its weight, protect its set point. And like I just said, allow you to survive, allow you to procreate. So then you put basically our ancestors' genes in the modern day environment, you've got these evolutionary mismatch. Like I also mentioned, we can't say no to our favorite foods. We keep going to dinner, having the desserts, we do it at home. Um, and as a result, the weight starts to go up over time. Our body's just not designed to be putting these energy dense, low nutritious foods into our body every day. You can have them and they play a role. Food is to be enjoyed, but they're just not the everyday foods, which is what they've become, um, in, in, you know, 2021.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, absolutely. And I, I imagine there is a degree of variation between different, um, people and backgrounds, right? So Australia has a large Aboriginal community that have largely unchanged their, um, uh, what they eat for, for, you know, thousands of years. And they are particularly vulnerable to the changes in the modern day environment, whether it be alcohol or the refined sugars as well. Is that something that you've seen in your clinic?

Dr Nick Fuller: Yeah, absolutely. This is a very good point. I mean, um, they are extremely vulnerable and, um, then what we end up seeing is much poorer health outcomes with these population groups. So there's a lot of work to be done there with certain community groups, um, and our indigenous population. And, you know, not only equipping them with the education, but also the support tools. Um, because you do see this vast disparity in, in not only prevalence of overweight and obesity, but other health outcomes. And that could be related to, um, different, you know, social factors in our life.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, absolutely. You, you sent over this paper that I've, I've come across, I believe before during my master's in nutrition. And I, I love going into the, um, physiological responses and the biological protections for weight loss. And there are eight different well-researched processes, but obviously we don't have time to go through every one. And if people are interested, I'll, I'll definitely link that to the show notes. Um, but I wanted to speak specifically about energy expenditure, um, so the total energy expenditure and how we calculate that and, and how that's related to, um, the, the weight gain that we're seeing. I mean, you spoke about it before about, you know, how we've become a bit more sedentary, but I wonder if we can go into a little bit more detail about the, the that equation that that gets, uh, that used quite a bit.

Dr Nick Fuller: Yeah, this is a fascinating one. And, and this sort of stems from a lot of my earlier work, uh, when I was working behind the scenes on, on these TV shows. Uh, basically, if everyone thinks about their body and it being an engine, that engine has a motor and that motor can be referred to as your metabolic rate or your metabolism. How long, how quickly it's ticking along every day. So for some people, it's going to be revving along, um, particularly those that have high muscle mass to body fat ratios. But then other people that have higher body fat to muscle ratios are going to have slower metabolisms because muscle is more metabolic, more metabolically active, which means you burn more energy at rest. But what the, the real fascinating part about our metabolism is that, sure, it's the, the number of calories you're burning at rest, but when you go and lose weight, you're losing body mass, so you're losing some fat, you're also losing some muscle. And we can account for that. We, we know that your metabolism is going to go down because you have less body mass. You have less, uh, stores to burn. Now, we can account for that as scientists, but what we also find is that there's a further 15% decrease in metabolism that we can't account for, that we have really no idea as to why this is happening. Now, a really good example, tying it back to the TV show, um, is the biggest loser. Everyone knows this, um, it's, it's hit, you know, most countries throughout the globe. And a very clever scientist by the name of, um, Dr Kevin Hall followed up the contestants from this show. And at the start of the show, they have a metabolism or a metabolic rate, their engine was revving along with about 2,600 calories per day. They then lost a significant amount of weight and their metabolism went down to about 2,000 calories per day. He then followed them up six years later, and despite the fact that most of them had regained the weight, their metabolisms had not recovered. It was at 1900 calories. It was actually less than what it was when they'd lost the weight. So not only did they see the decrease in metabolism, but they had a further decrease by about 15%. And then even after they regained the weight, their metabolism or metabolic rate stayed low. And why people might be thinking, why, why, why? Well, remember, this is because this is our evolutionary desire to survive, to protect our set weight. It doesn't know any better. It is shutting down in order to survive and procreate. So what you're seeing is this reduction in metabolic rate, but you're seeing a reduction by 15% more than what you should, which means you're going to burn less calories at rest. You're just fighting the weight loss. Inevitably, your body claws back to your start point. And that's the real sad part about it. Your body thinks it's working in favour or working for you, but it's working against you. And it's the real reason why we're, we're struggling long term.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, definitely. You know, there are so many people listening to this who can probably resonate with that typical story of starting a diet, having some fantastic results, feeling super motivated, falling off the wagon when it comes to eating well every day, plateauing, and then seeing that weight come right back up. And that one physiological mechanism of which there are many, like you've just mentioned there, is an explanation as to how and why that happens. And I think, you know, before people sort of, um, uh, get too despondent about why their body might be different, I think it's quite comforting to know that this is our biology and this is almost going to happen if you enter into a short-term restrictive diet.

Dr Nick Fuller: Yes, absolutely. So, you know, this is something that's very important for people to realize that you're not failing due to a lack of willpower. Sure, you might follow some programs that are unsustainable and, you know, telling you to cut out certain food groups and foods which you can't adhere to long term. But what is most important is that you understand that you do have your biology fighting itself and your body is fighting that weight loss. And this is why, you know, a lot of this education does help empower a person so that they can understand why they've been getting these same results year in, year out. Not only themselves, but also the stories they hear from friends, family, and colleagues. The real problem we have is that a lot of these diets, not only do they have, are they backed by big name celebrities and social media sensation, but they're self-validated by that quick instant gratification that people get on the scales. So I go and follow, for example, a low carbohydrate type approach. Carbohydrates bind a lot of, um, glycogen binds a lot of body water, um, which means that when you strip them, number on the scales goes down. So guess what? We celebrate. Sure, there's a lot of other factors going on as to why the weight loss is coming quickly and rapidly with such approaches and different diets. But eventually, what we don't talk about and what we don't hear about is the long-term pain that people are suffering from. So they go out, they celebrate the short-term wins, but then slowly they're going to be clawing back. And this is what we're seeing in our hospital clinics. We're seeing people come in and we're seeing the long-term ramifications and repercussions of long-term dieting. Um, and I'm not saying that, you know, all diets or all weight loss programs are bad. Sure, there's definitely better ones and some that achieve some fantastic results long term. And we can also get into that later on. But what people need to know and equip themselves is with this education so they can appreciate that the short-term fix, the short-term win is not going to help you necessarily with your long-term goals. You're going to have your body fighting itself. And the reason you're failing is due to your biology and these eight well-researched physiological responses that take place the minute you sign up to a diet.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, yeah, definitely. And you know, I was really interested to learn a bit more about how there's an increased responsiveness to food with, um, reduced intake. So it's almost like your cravings go up as you lose more weight. Um, and there's that impairment, I guess, to, to see when you're full as well. Can we go into a little bit more detail about what that happens and is it a phenomenon or is it something that something that can be explained?

Dr Nick Fuller: Yes, this is a, this is another fascinating piece of research. Um, and it sort of covers a few different areas, so I'll keep it as succinct as possible. If we think about the appetite regulation system, so remember at the start I said before the 1970s, that sort of crude time point, we had a very, we did a good job at keeping ourselves in a healthy body weight range. That clever wiring system between, you know, our stomach, gastrointestinal system, and our brain, um, acting on the hypothalamus telling us when and when we shouldn't eat, it worked perfectly fine. But then the environment changed, hedonic pathways kicking in, reward means that you go back for the dessert time and time again. Now, what happens with weight loss is you disturb or you muck up this appetite signaling system. So you lose weight, and you know, that, that hunger hormone, those hunger pangs that everyone talks about, well, that's ghrelin. That's an appetite hormone that's released peripherally, acting on the brain, acting on the hypothalamus telling you to eat. Now, when you lose weight, ghrelin levels go through the roof. This is not a subjective feeling. This is objectively happening. We take blood measures from people, we measure these appetite hormones, and as they lose weight, ghrelin levels go up telling them to eat more. Now, you also have other appetite hormones working to, um, you know, tell you to basically continue with food. So you see a suppression of PYY, GLP-1, leptin, you know, basically they're ones that usually tell you to terminate food consumption. Well, they're suppressed, switched off, so you continue to go back for more and more food. So this is not a subjective feeling. People, when they say I just feel ravenous when I'm, when I'm dieting, sure, you know, many of them are following very strict, low energy diets and not enough, um, they're not consuming enough food. But most importantly, they're going to be seeing this change in their appetite signaling system. They're going to be seeing the ghrelin levels go through the roof, the hunger pangs, um, are going to be experienced and that's going to make you go back for more and more food. But it also ties into what we briefly talked about, um, with the brain activity. So you do see a heightened response of those foods that you cut out with when you diet. So for example, you sign up to a diet and tells you to cut out all of those favorite treat foods. Sure, we know we can do this, but we can only do it for a short period of time. And again, that's due to evolution. So we can cut them out, usually between four and 12 weeks, um, which is why you typically do see these cute, neatly packaged four, eight, 12 week online weight loss programs because that's how long you can succeed before then giving into your cravings. Uh, the what the hell effect comes into play and you end up eating the whole packet of, in Australia, Tim Tams instead of just the one Tim Tam. So, I've lost some weight and my appetite's going through the roof, the ghrelin levels are out of control and I'm reaching for the Tim Tams and I'm eating and devouring that whole entire packet. Um, my brain activity is changing, the emotional response, um, to food, you know, all of this is changing within the brain so that you go and seek out high fat, high sugar foods. Remember, you switch back the clock tens of thousands of years and that's what we used to seek out, again, in order to survive and procreate. We would seek out the high sugar, high fat foods, gorge when they're available, store them, and then go through the motions, um, day in, day out. So it's no different. Remember, you've got these evolutionary mismatch, but you can cut them out for a certain period of time, but eventually, uh, your body is changing, it's going to tell you to go back for more, and your appetite signaling system is, is being disturbed so that your hunger goes through the roof and you eat more food inevitably so you claw back to your start point.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, definitely. You know, there's so many fascinating, um, snippets of this, you know, that I've learned as well along my journey. The fact that your, your body fights the weight loss, um, and, you know, people aren't failing. It's, it's how we've been designed, uh, and there is this sort of biology, a biological imperative, I guess, to, to regain that weight, um, because it's a protective mechanism. Um, and I, and I always like to use that sort of evolutionary lens whenever we talk about weight or health or, you know, nutritional medicine in, in all different aspects because it is, it's super important to understand why we get ourselves into different situations.

Dr Nick Fuller: Yes, it's, it's, um, something for a long time, I guess, we have as, as a, you know, across the globe have always thought that we just keep failing because of that lack of willpower. Um, and, you know, the dieting industry do a very good job at sort of, um, selling that as well. But like we're describing, it is due to your biology and it's something that's outside of your control. Um, but there is no point in fighting it. You fight it and it's going to win and it's going to win every single time. And this is why you keep seeing the same results, week in, week out, year in, year out, and why you're in the same position you've been in for the last couple of years, 10, decade, whatever it might be. Um, but you've got to, yeah, be empowered that it's, it's not definitely not your fault. Um, you can regain control of your health and weight, but you need to understand how your body works. It's quite fascinating. It's a, it's a marvelous, um, I guess, bodily system and, and the way it works to protect itself against weight loss is really just that, it is remarkable. And I guess the, the point to, um, highlight there is that it's not always related to these extreme weight losses. We know that a clinically significant amount of weight lost, about three kilos, 5% of your body weight, is when your body starts to fight itself. That's when your body starts to work differently. It's a very small amount. So it's not the, you know, the biggest loser contestants where they're losing the 20, 30, 40, 50 plus kilos. Um, we're seeing patients in our clinics that only have to lose a couple of kilos and then we have patients that are 200 kilos plus that have to lose a significant amount of weight. So for everyone, it's just a small amount of weight loss when your body starts to fight itself. And when that happens, you've got no chance of fighting it.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, definitely. You know, I got a message from a whole bunch of people after I did the the last, uh, weight podcast that went out. And and one of them was, um, I've anonymized her, but she said, hi, I was hoping if you could put me in the right direction. I've just been reading your post about the latest podcast. I'm 42, completely miserable about my weight. I'm two stone over and no matter what I do, I can't even lose a pound. I actually think there's something wrong with me. And she goes on to talk about how this is obviously having an impact on her emotionally, um, and, uh, and and where to get help. And I think it's, you know, when I think about weight, yes, I think it's important to think about the extremes and how we help, um, those people caught in that in in that around that issue of of extreme weight, um, uh, gain. But I think there's a, there's an underbelly of people who are sort of tipping into that pre-diabetic, morbidly obese, uh, range that we need to protect, particularly in the NHS here.

Dr Nick Fuller: 100%. And, um, you know, this is, this is a very typical, uh, sort of story that we're getting as well. One that they're describing, they can't lose weight anymore. I suspect they've tried numerous different things and, you know, it is always full kudos to them because they're out there and they're trying. There's, that is not the problem. Um, they're going back and trying the same programs time in, time out, but then they just think they're failing due to that lack of willpower. Uh, so yes, it there's a really big piece of the puzzle that we need to to fill here with education to around those people that only have a few kilos to lose, um, that are at the other sort of the normal to overweight end of that spectrum. Remember, we've also got this other story going on, um, in terms of the young population, okay, buying into, um, again, this distorted, uh, body image story and dieting themselves heavier and heavier. So it's sort of now widespread. Um, it's from young through to, uh, definitely, you know, mid-age because after later on in life, you typically see a little bit of a weight decrease, um, anyway, and it could be protective against certain disease and and death. But yes, that is an important part of the puzzle that we need to be able to complete so that people can prevent getting to this stage where they're completely out of control because otherwise they will end up at that point. Plus, they're wasting so much time and effort and money on all of these different approaches that aren't going to help them. They're miserable, they've got this poor relationship with food. They've lost interest in so many different things. You know, health and, and, and lifestyle, all of these things, food is there to enjoy. Um, and I guess a lot of this information that's that we're getting told day in, day out has led us to believe that, you know, what is there now, what is there hope for? Um, and, you know, certain foods are bad for me and I should stay clear of them. But a lot of it is nonsense, it's misleading and you've got to sort of block that out and, and, and move forward.

Dr Rupy: Epic. Well, that's, uh, I, it's been fantastic chatting to you, Nick, uh, and, uh, I can't wait to share a coffee and a, a Tim Tam, uh, next time I come to Australia.

Dr Nick Fuller: Yeah, likewise, likewise. I, you know, I love, love your work, um, big fan of of your podcasts. It's a, it's a real pleasure to be on. Um, and and I hope, you know, through this, you know, the listeners are educated, um, and and can sort of make some informed decisions now and and realize that, look, dieting can do a lot of harm. Um, you can, you're going to shut down your body's physiology, but you can restore that damage and you need to follow evidence-based care. You can jump online and there's plenty of materials, um, on this interval weight loss program, so you can start to educate yourself, learn these six principles, because, yeah, look, you may not have to tackle all of them, but most of us, you know, in that sort of six simple steps is something that's out of whack. It could be the food addiction, it could be the lack of exercise, it could be the poor sleep. And it's about implementing and giving you, equipping you with tools so you can make this part of your day-to-day life.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, definitely. Yeah, we didn't even get a chance to talk about all the other, uh, determinants like sleep and exercise, uh, to to weight maintenance. But I'm sure, I'm sure we'll, we'll try and get you back on the pod at some point in the future. It's been a pleasure chatting to you, Nick. And, uh, I can't wait to, yeah, no, I love the work. Love your work and the, the feeling's mutual.

Dr Nick Fuller: Thanks, Rupy. Appreciate it greatly and look forward to that coffee and Tim Tam.