Is our nutrition information accurate?

27th Oct 2022

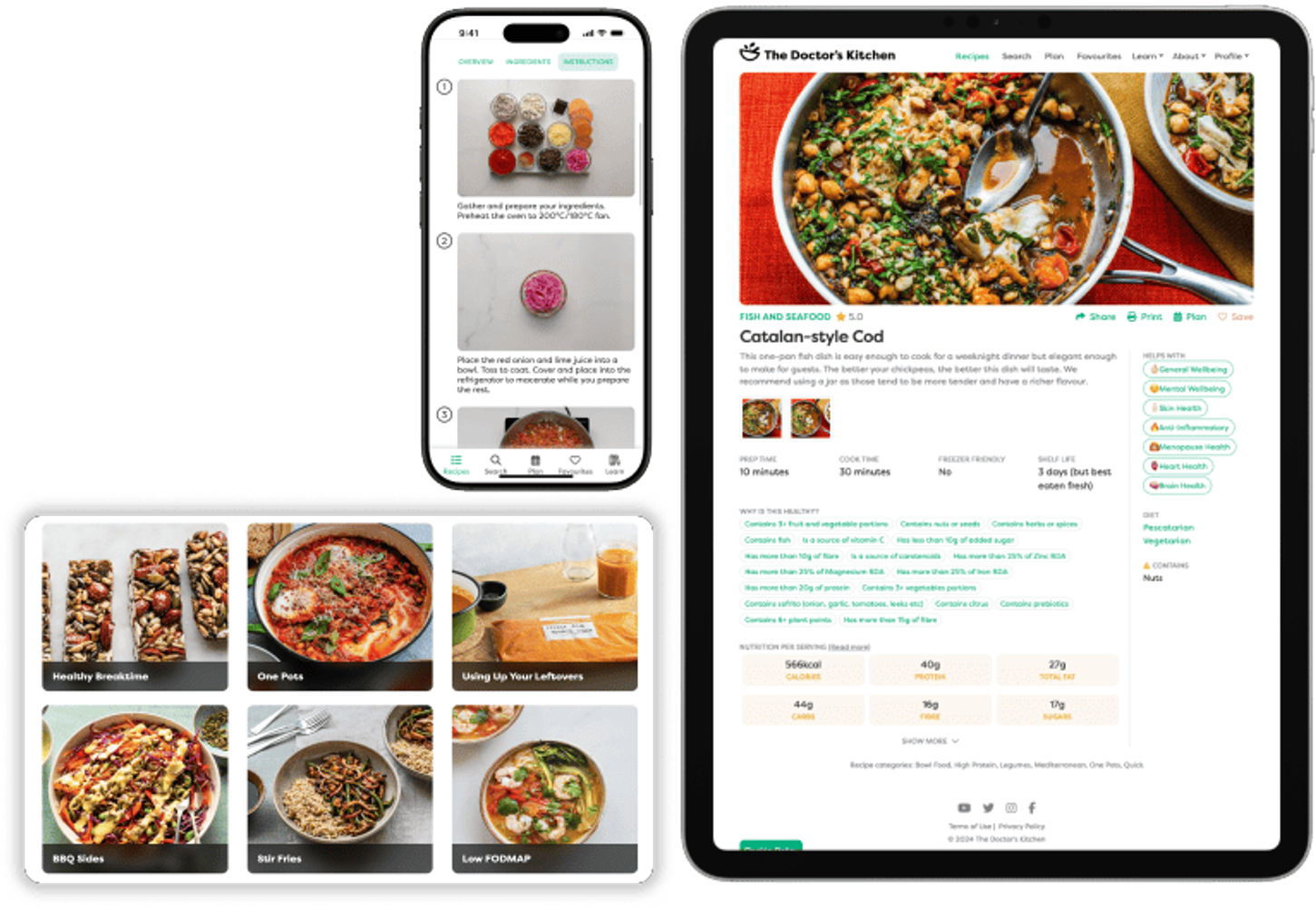

We recently created our nutrition calculator for the Doctor's Kitchen app. It provides nutritional information for every recipe, including calories, protein, fibre, vitamins, and minerals. Here’s how we ensure reliable values for our recipes.

Key points

Why did we build our nutrition calculator?

Previously, the nutrition information displayed in the app was sourced from external online calculators. We would manually input each value for every recipe in the app. Other than being time-consuming, this process relied on data we knew little about. We curated our own food dataset and nutrition calculator in the app to improve the accuracy, reliability and transparency of the data we use.

How does it work?

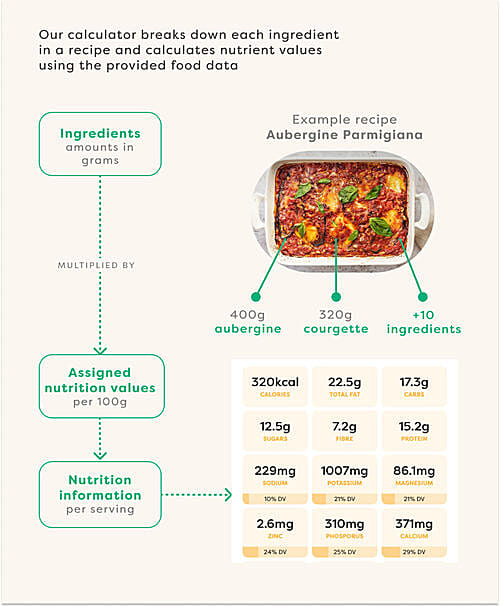

Like other nutrition calculators, it works by breaking down the amounts and nutrient values for each ingredient in a recipe and calculating the total nutrient values – including calories, protein, fats, carbs, sugars, fibre, minerals and vitamins. It requires quality nutrient data for each ingredient and an appropriate calculation method.

Why you can trust our nutrient values

✅ Reputable sources: The nutrition data in our app is taken from reputable sources, including:

- Government databases like the U.S Department of Agriculture (Food Data Central) and Public Health England’s Composition of Foods Integrated Dataset (CoFID)

- UK product labels

- Research papers

- Phenol Explorer

✅ Well-defined selection criteria - There are many nutrient values available, even for simple ingredients. We carefully select values for each ingredient based on 4 criteria:

- Precooked raw values to account for differences in cooking times that can result in different weights. This principle excludes food items that you buy cooked like pre-cooked rice and canned beans.

- Consistency: Is the data consistent with other reputable sources and UK products? We compare a large proportion of our data with multiple reputable sources and products found in common UK supermarkets.

- Most complete data: When available, we chose the most complete data and recent update. Some food data was analysed in the 1980s with no recent update, which increases the chance of inaccuracies. Where available, we chose the most recently updated data.

- Relevance to our users: For some ingredients like pastes and sauces, we relied on “branded” data from food labels. We opted for healthier options with lower sugar and sodium content.

✅ Regular checks and updates: Our team is regularly reviewing our nutrient values by comparing them to other sources to make sure we’re providing trustworthy nutritional information. If you use the app, give us feedback and help us identify any discrepancies.

Where we’re heading

As we’re working hard to provide quality nutritional information, we’ve come across some hurdles regarding the accuracy of nutrient values. Read more about why nutrient values are inherently wrong. Here’s what we’re thinking about next…

- Adding more values, like phytochemical content and plant points.

- Ranges over single values? While providing single values for nutrient content has been standard practice, we’re exploring the option of presenting ranges to account for natural variations. For example, the protein content in walnuts can range from 14 to 17 grams per 100g. This way, we would give you a more realistic picture of nutritional content.

- Beyond nutrient values…We’re also thinking about more integrative ways to provide information about the health effects of foods, beyond standard nutrient values.

👉 To be part of our exciting improvements, download the Doctor’s Kitchen app for free here.