Thyroid Disease

25th Feb 2021

All you need to know about thyroid disease

Key points

Thyroid gland

The thyroid gland is located in the front of your neck and plays a key role in producing a number of hormones. These affect your heart rate, basal metabolic rate, and body temperature.

Thyroid Disease

If your thyroid gland is not functioning correctly, this can lead to problems. This is either in the form of an overactive thyroid gland (hyperthyroidism), where your body produces too much of these of hormones; or underactive thyroid gland (hypothyroidism), where your body does not produce enough thyroid hormones. Normal production of thyroid hormones is called euthyroid.

Both overactive and underactive thyroid disease can be caused by autoimmune diseases, where your body mistakenly attacks itself. Grave’s disease leads to hyperthyroidism, while Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, leads to destruction of the thyroid gland resulting in hypothyroidism. It is caused by an increased level of antibodies against thyroid peroxidase and thyroglobulin. A viral infection, certain medications or even after having a baby, in rare cases, can all increase your risk of thyroid problems.

For more information about thyroid disease and the symptoms see the NHS guidance.

Treatment

For people with an underactive thyroid, the mainstay of treatment is replacement of the hormone thyroxine via medication.

Treatment for an overactive thyroid gland depends on number of factors, but options are medication, surgery or radioactive iodine treatment.

Nutrition and Thyroid Disease

Iodine

Iodine is a micronutrient commonly found in seafood and milk. It is necessary for the thyroid gland to function optimally, but too much iodine long-term can be toxic and may actually induce autoimmune thyroid disease.

For pregnant women, having enough iodine is important, due to the role in foetal brain development during pregnancy and early life (1). This highlights the importance of adequate iodine levels, not too much or too little.

While the basis of most thyroid disease is unknown, genetic susceptibility, environmental factors, and immune disorders are likely to contribute to its development. There is some evidence that suggests that the onset of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, may be associated with high iodine intake and deficiencies of selenium, iron and vitamin D, but much more research is needed (1).

There is no need to take iodine supplements if you are taking levothyroxine for hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid) or for a goitre (thyroid swelling). If you are being treated for hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid) taking an iodine supplement is unnecessary and can worsen the condition. The extra iodine can counteract the benefits of the anti-thyroid drugs.

Selenium

There is evidence that the mineral selenium may reduce thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibody levels in hypothyroidism, and postpartum thyroiditis (1). Foods rich in selenium are brazil nuts, seafood, meat and eggs.

Iron

Iron deficiency may impair thyroid metabolism. Thyroid peroxidase enzyme that produces thyroid hormones, needs iron to become activated. People with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis may also have autoimmune gastritis, which impairs iron and B12 absorption. In people with persistent symptoms of hypothyroidism despite treatment with levothyroxine, supplementation of iron and vitamin B12 may help (2).

Vitamin B12

Autoimmune thyroid disease is also associated with other autoimmune disorders such as pernicious anaemia and atrophic gastritis. Both of these may lead to decreased absorption of vitamin B12, which should be checked if you have autoimmune thyroid disease.

Kelp and Seaweed

Kelp and seaweed are very high in iodine and may interfere with thyroid function. They are sometimes marketed as a “thyroid boosters”, but are not beneficial, particularly to those with thyroid disease.

Gluten

While there is an increased risk of coeliac disease in people who have autoimmune thyroid disease, there is no evidence that exclusion of gluten has any role in thyroid disease or hormone production. Therefore, unless you have coeliac disease, you do not need to exclude gluten from your diet.

Weight Changes

Since thyroid hormones have an important role in basal metabolic rate, weight changes are frequent.

Weight loss is seen in the majority of people (90%) with hyperthyroidism prior to treatment. Weight gain is frequently seen in both untreated hypothyroidism and also after treatment for hyperthyroidism, as the weight lost is prior to treatment is re-gained.

Additionally, post treatment of hyperthyroidism and return to normal levels of thyroid hormones (euthyroid), may unmask a predisposition towards obesity (3).

Other risk factors commonly implicated for such weight increase include the severity of thyrotoxicosis (excess of thyroid hormones) at presentation and underlying Graves’ Disease (3). Potential weight gain can be mitigated by adapting a healthy balanced diet during and before the start of treatment (3).

Vitamin D

Some studies have found an association between low levels of vitamin D and thyroid disease, but it is not known if there is a causal relationship (4).

One randomized controlled trial found that vitamin D supplementation in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease was associated with a reduction in anti-thyroperoxidase antibody (TPO-Ab) levels (4). However, much more research is needed to investigate whether this is associated with improvement in thyroid disease. Instead, it is a good idea to follow NHS guidelines with regards vitamin D supplementation.

Absorption of Levothyroxine

Levothyroxine is the primary treatment for hypothyroidism. A high fibre diet can decrease absorption of levothyroxine (5). Some calcium rich foods and supplements can also interfere with levothyroxine absorption. Try to ensure a gap of 4 hours between them and taking levothyroxine medication.

Soya can also interfere with levothyroxine absorption. Therefore, if you are taking levothyroxine you should try to avoid soya. If you wish to take soya, there should be as long a time interval as possible between eating the soya and taking the thyroxine.

Some medications such as iron tablets (ferrous sulphate), may interfere with the absorption of levothyroxine. Up to a two-hour interval between iron and levothyroxine is recommended, but you should follow the advice of your doctor or pharmacist.

Brassicas vegetables such as cabbage, cauliflower, and kale, may contribute to the formation swelling or enlargement of the thyroid gland (goitre) in some cases. However, consumption would have to be extremely high before this would be concerning. The risk is very low with a normal diet.

Summary

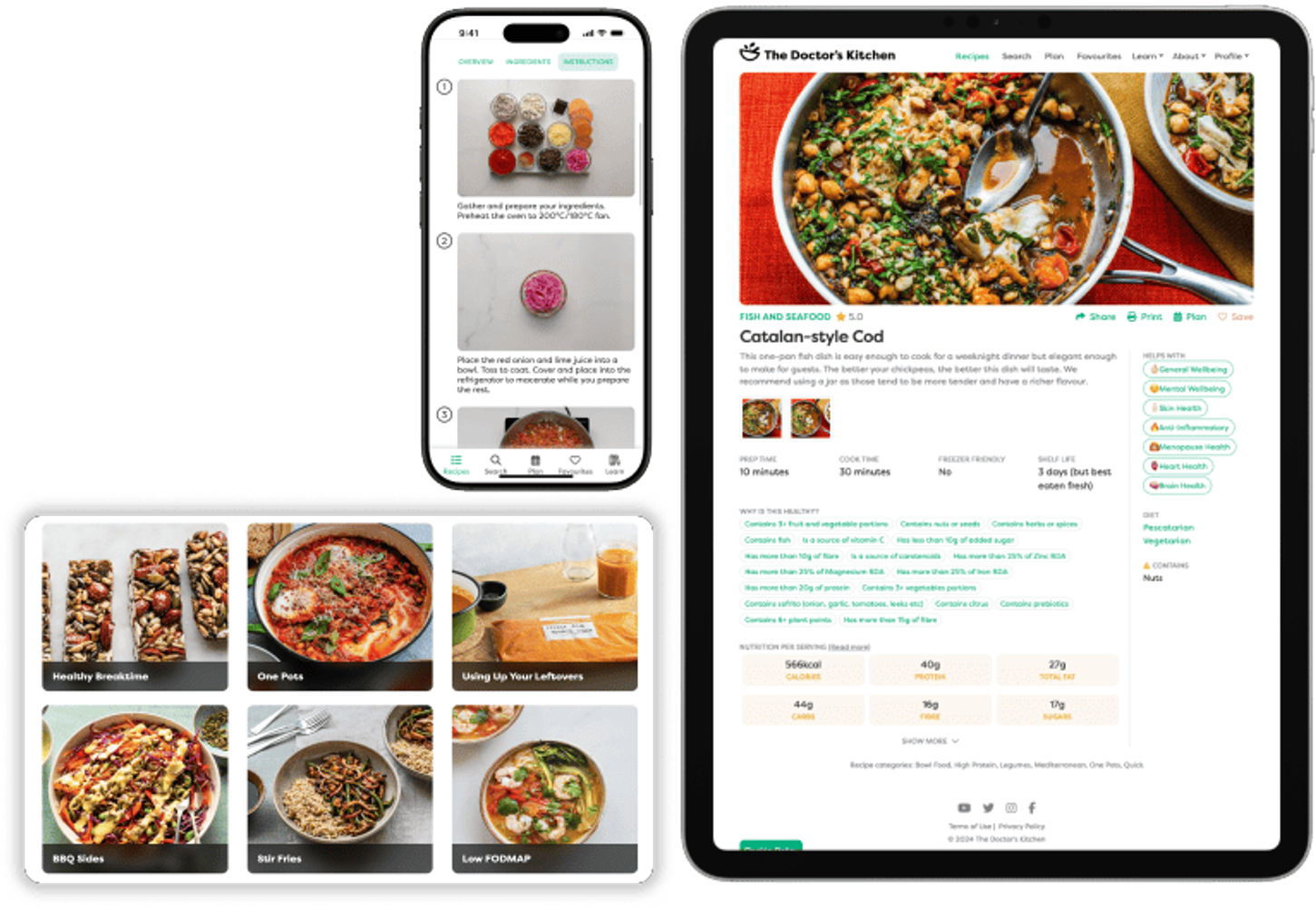

Sadly no dietary changes can cure thyroid disease. However, given that weight changes are frequently seen with thyroid disease, adopting a healthy diet, that meets your micronutrient needs is still important. Aim to have a diet that includes:

- A range of fruit and vegetables

- Try to eat more unsaturated fats

- A handful of nuts and seeds a day

- Consume oily fish twice a week

- Swap refined carbohydrates for whole-grain carbohydrates

- Supplement with Vitamin D according to NHS guidance

- Lean protein

- Iron rich foods such as beans, meat, dark green leafy vegetables

- Beans and pulses

If you take levothyroxine avoid:

- Soya

- Taking iron supplements within 2 hours

- Consider reducing your fibre intake if you have problems with absorption

- Taking calcium rich foods (fortified products, dairy, fish with edible bones) and supplements within 4 hours

Article Credit:

Dr Harriet Holme (https://healthyeatingdr.com/)

References

- Altieri, B., Muscogiuri, G., Barrea, L., Mathieu, C., Vallone, C. V., Mascitelli, L., et al. (2017). Does vitamin D play a role in autoimmune endocrine disorders? A proof of concept. Reviews in Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders, 18(3), 335–346.

- de Carvalho, G. A., Paz-Filho, G., Mesa Junior, C., & Graf, H. (2018). Management of Endocrine Disease: Pitfalls on the replacement therapy for primary and central hypothyroidism in adults. European Journal of Endocrinology, 178(6), R231– R244.

- Hu, S., & Rayman, M. P. (2017). Multiple Nutritional Factors and the Risk of Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis. Thyroid : Official Journal of the American Thyroid Association, 27(5), 597–610.

- Kyriacou, Angelos, Kyriacou, A., Makris, K. C., Syed, A. A., & Perros, P. (2019). Weight gain following treatment of hyperthyroidism-A forgotten tale. Clinical Obesity, 9(5), e12328.

- Rayman, M. P. (2019). Multiple nutritional factors and thyroid disease, with particular reference to autoimmune thyroid disease. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 78(1), 34–44.