Karen: 60% of the seeds that are legally allowed to be traded worldwide are owned by four companies, which are doing bad, bad stuff to the soil.

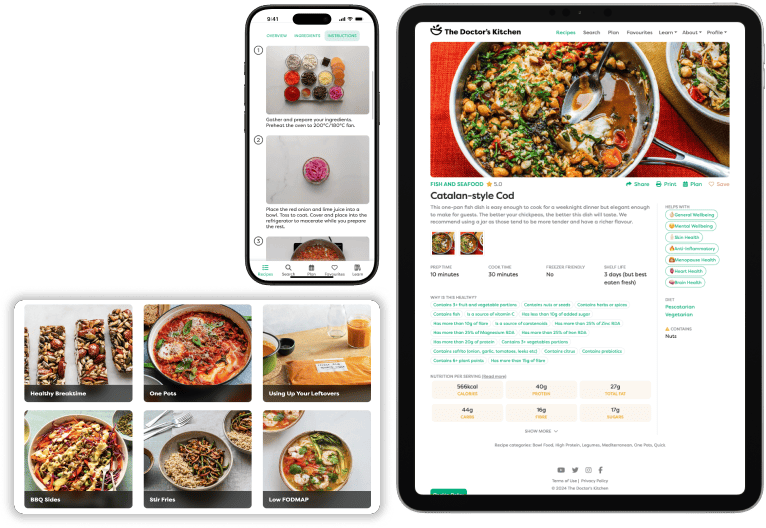

Dr Rupy: Welcome to the Doctor's Kitchen podcast with me, your host, Dr Rupy, where we discuss the most important topics and concepts in the medicinal qualities of food and lifestyle. This podcast is the place to be for anything to do with nutritional medicine and how we can use both food and the way we live to prevent and manage ill health, as well as maintaining your optimal wellbeing. My guest today is Karen O'Donoghue, the founder of the Happy Tummy Company, which she established in Hackney, East London, back in early 2014. I've known Karen for a number of years. She is an absolute breath of fresh air when it comes to the wellness industry. She doesn't talk any doodoo, and she doesn't hold back either, and that's why I really wanted her to jump on the pod. She actually suffered from chronic IBS symptoms since childhood that was constipation predominant. We talk a lot about that in the podcast, actually, and how she, after looking at research articles, found out about the microbiota and how important gut bacteria is to general wellbeing, but particularly for IBS, and using what has now been described as the magic poo bread was able to rid herself of the IBS symptoms. And she started sharing the bread recipes and then actually supplying it, and has helped thousands of people get more connected with their bodies as well as improve their IBS symptoms. And she has a personal mission, which is to eradicate the world of IBS. She is an activist for fibre, for real bread, and now she's moved to East Sussex where she's opened a bakery school in the countryside surrounded by farmland, herds of cattle and sheep. It is really idyllic, and I can't wait to go and visit her, which I 100% will. If you want to see the recipe that I made for Karen on the podcast, just jump on to the Doctor's Kitchen on YouTube. I made her this delicious Iranian-style stew with beans and pomegranate molasses, fresh pomegranate, rose petals that gives a lovely perfume to it. I think you're going to really love this recipe. It was super easy to make. And the reason why I made a stew is because I wanted to dip her wonderful toasted bread in it. And honestly, it was just an amazing experience. Go check it out. You can see how to make her bread on her website as well. We talk about a lot of different topics on this podcast: her journey, the importance of seed banks, maintaining an open and respectful perspective on different types of farming methods as well. She is really, like I said, a breath of fresh air because she has certain views on organic farming that I think will become a lot more popular as we gain a lot more evidence about the need for proper crop rotation. I learned a lot on this podcast, actually, about the importance of soil, because if we are interested in human nutrition, then we should also be interested in the quality of the plants that we create. And thus, we need to be interested in the health of our soil, the soil biome, which is a living, breathing thing. It is the medium by which we are able to create these incredible products that have all the different chemicals as well as minerals and vitamins. And without healthy soils, we cannot create healthy food for humans to consume and prevent ill health. Remember, you can check out the recipe I made over on YouTube and all this information and more at thedoctorskitchen.com. And whilst you're there, subscribe to the newsletter for weekly science-based recipes. For now, I'm going to stop talking and we're going to get on with the podcast. Karen, thank you so much for coming to the kitchen, all the way from Sussex.

Karen: Very welcome. Very welcome.

Dr Rupy: All right, we're going to get into it. I'm going to, I've made this meal because I want to try your delicious bread with it. It's a simple stew. It's going to be some cannellini beans, but you could use chickpea or red kidney bean, whatever beans you want. We're going to go in with some passata, just plain passata, some barberries, which you can get from most supermarkets these days. It's like this tart berry. I love it. Have you used these before?

Karen: I love barberry. Yeah.

Dr Rupy: Have one of those. It's kind of like a, the anti-goji berry. It's tart, it's lemony, it's gorgeous. Yeah. Um, rose petals for some sweetness, and some pomegranate molasses as well. We're going to get cracking with that. I'm also going to add some coriander seeds, some cumin seeds to this pan, and everything's going to go in one pan. It's going to be super easy.

Karen: Amazing. I love a one-pan dish.

Dr Rupy: Exactly. Yeah. Um, and the whole reason is because we want to try your delicious bread and stuff. So, yeah. Thanks for coming down, like I said.

Karen: Very, very welcome. Very, very happy to be here.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, we've known each other.

Karen: Making food with you.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, actually, I was thinking about this, right? So we met three years ago on February the 5th at a Fair Healthy thing, and you were there supporting Dr Hazel.

Dr Rupy: Yes.

Karen: Um, and I was on a panel with Hazel at the time talking about grains.

Dr Rupy: Yeah.

Karen: Um, and I remember actually, so yeah, that was three years ago. And I remember being on that panel talking about crop rotation, and everyone in the audience was just like, mind blown. And I'm just like, I feel like this is a normal, you know, this is like a normal sentence within this subject, but yeah, I think, um, at that time, anyway, certainly farming and horticulture and like the growing of our food felt quite distant from the eating of the actual food. Um, and yeah, maybe I miscalculated that at the time, but I feel like now when you talk about crop rotation, it, um, yeah, it means a lot more to people.

Dr Rupy: On, honestly, that day, you, I mean, like, I don't think you, you ever don't speak from the heart, but you certainly were the most impressive in terms of like the people that I saw on the stage, um, that day. And it's just because you were being so genuine about everything. Like everyone else is kind of like, you know, dancing around the subject, but you were just like, no, this is what we need to learn. We need to learn about our culture and how we actually need to grow things and what the importance of the soil is and grains and, you know, a massive champion for bread. I was like, finally, in this gluten-free world of restriction that's religiously focused on carbohydrate restriction. Yeah. You were championing, you know, something that has been responsible for the, the mass globalization of our human race, you know, bread, essentially. So, and I was just like, yeah, that's great. Like, and that, I think I reached out to you after that.

Karen: Yeah, yeah, yeah. And I remember, yeah, meeting you afterwards and just being like, oh my god, this guy is so energetic and like, and yeah, then when I learned more about your culinary medicine and everything you were doing, I was just like, oh, this is so amazing because, um, I mean, yeah, so my sister is a GP and like, you know, I hear all of her stories and I hear about people coming into her and like, you know, she's just telling them to like eat a better diet, like do not smoke, get exercise, like. Um, and then meeting you and you kind of aligning the two so well and so eloquently and so progressively, if I'm honest, it was just like, ah, there's hope for the world. You know, there's.

Dr Rupy: You moved out of, um, central London, like.

Karen: In July.

Dr Rupy: In July. Yeah. How's that transition been for you?

Karen: Um, so, um, okay, so one of the things is I've actually moved to a place where the soil is clay. So it's actually really difficult to grow food. Um, so I wasn't as aware of that movie as I should have been. Um, and, uh, so to grow food where I live, you actually have to like use loads of compost. You know, you're kind of building up the soil as opposed to digging down. Which actually kind of goes against the way I think about food. So I want to dig down and that's what I'm used to. You know, I grew up in Cork in Ireland where my parents ran a horticulture company. My father still runs it. Um, and every Easter we used to plant thousands and thousands of saplings. So for me to like now work on building up the soil and then dig into that pretty loosely feels a little bit, um, unintuitive. Um, but outside of me having horticulture challenges, um, yeah, it's been, it's been really, really, really amazing. It's been really amazing to get, um, a lot more perspective on, uh, what a friend of mine coins weather weirding. Um, so that's been quite interesting.

Dr Rupy: So instead of talking about climate change, because he's like, well, the climate is actually still the same. He's calling it weather weirding, which I quite like because it explains, you know, we get like these like horrendous bouts of rain in Sussex, we get horrendous bouts of flooding. And it's like, ah, is this, this is weather weirding, right? So it's, I don't know, it just like, it, it makes the topic of climate change a bit more, uh, community-based and something we can kind of solve from the ground up as opposed to like, you know, all like the countries around the world are going to come together and like solve climate change. Like that's not going to solve climate change. Climate change will be solved through like better farming, um, you know, better purchasing from kind of communities, um, and bringing things, um, more local again.

Dr Rupy: So this combination of like small changes, community action that grows from the soil up to part of the pun is definitely the way in your mind that you think.

Karen: 100%. I am so convinced of that. So, um, I guess up until now, and I feel like we are in a changing time, up until now and certainly post World War II, um, let's take Britain for example, because here we are in Britain. So, um, in the 1970s, uh, when Britain became part of the EEC, um, we kind of had to get on board with this, I suppose, European community of trade. So because of that, um, farmers that were farming wheat, for example, had to register the seed that they were growing, um, on this national list, um, and then they were legally allowed to grow this seed. So, basically overnight, uh, we kind of went from farming thousands and thousands and thousands of varieties of loads of crops, uh, pretty much organically, to a really, really, really small selective group of crops. Um, and, uh, these crops, um, because obviously, during the war, we lost millions of people. Um, the way to farm was like, um, yield is everything. So we are going to farm for yield, yield at any cost was kind of the motto of the government. Um, and that's fair enough because people, you know, people were dying of starvation, you know, we had lost a lot of people. So yield at any cost made sense at the time. Um, but yield at any cost meant, okay, well, we are dependent on, you know, the yield now being twofold, fourfold. Like if we don't get enough wheat, like our people are going to die. Um, and the only way the government saw fit to, uh, I guess, ensure this was to create herbicides and pesticides and all that kind of stuff to ensure, um, a crop would grow to a certain height, it was easy to manage, it was easy to harvest, um, and that, you know, I guess uniformity was kind of key to farming then. Um, and, and whilst that was good for feeding people and, and we got Britain to a point where, you know, we were nourished again, well, we were certainly fed, we maybe weren't as nourished as we could be. Um, I feel like then the government should have probably said, okay, we've done what we've achieved, we've like fed people, you know, we're, we're in a good stock of food now. So now actually, let's go back to looking at the soil health and, and making sure that we, you know, we save back seeds that are, you know, drought resistant or really vigorous and all these kind of things. But what happened was at that point, you know, corporates came in, they were privatizing seed banks, they were buying seed banks from government. Um, and, and, and, and really, really, really sadly, what happened was, you know, kind of commercial entities started cross-pollinating. Let's take a tomato plant, for example, because we were using passata today. So, uh, one tomato is drought resistant and one tomato is highly vigorous. Um, and, and as a company, I want a drought resistant, highly vigorous plant. So I cross-pollinate those. Um, so those are two kind of heritage seeds, you know, they've come from heirloom varieties that have been in, in, in that particular microclimate for, you know, hundreds of years. Um, and, and now I've made a hybrid seed. But unfortunately, with hybrid seeds, a lot of the time those hybrid seeds will never produce another seed. So you've kind of just got like this, like, this man-made way of like making food. Um, and then secondary to that, um, fertilizing and kind of inbreeding, inbreeding kind of seeds to, to kind of get all these like seven boxes or whatever it is ticked, meant that we also bred the root out of the plant. So this is like, what? Like, what have we done? This is nuts, right? So what we've done is we've created, um, you know, tomato plants, wheat plants, oat plants, uh, to have really, really, really short roots, whereby the straw is really short, because we want the machinery just to be able to like shave off the heads. Really, really, really short roots. So where's the nourishment going to come from? Um, and, and this, this straw that's above the soil, that's almost the same height as all the weeds as well. So we, we need like herbicides, pesticides to get rid of the weeds, because we, we don't have a wheat anymore that rises above the weeds. So, okay, so we've got wheat now with the same size as all the weeds, but now we've got a root that like can't search for nitrogen, can't search for water. Um, so this is really, really, really bad. Um, so now kind of what's happening is social mobilization amongst small communities, you know, have been petitioning government, um, and have been like, you know, going against the legislation saying, hey, we want to grow, um, wheat that goes way, way above the weeds so that the weeds can stay there. Like the weeds are fine. Um, and they'll just be crunched down in harvest back into the soil. Exactly. And then also, um, we want our roots to go into the ground again. We don't want to be, you know, we don't want to be feeding them. Like we just want the soil to feed them. So you would have a root that would be maybe four meters deep into the soil and, and then it had like fungi that like underneath that, that root that also like grew even deeper. So all these natural structures that were allowing, you know, just plant and the rotation of crop to just like function very, very well and sustainably was just eradicated overnight. Um, and the system post World War II to feed people never changed. So here we are in 2020 and we are, well, 60% of the seeds that are legally allowed to be traded worldwide are owned by four companies, which are doing bad, bad stuff to the soil. Um, the other 40% it's kind of, you know, a variety of small companies. Um, but excitingly, within that 40%, you know, there are lots of peasant farming across like South America in particular where social mobilization really took off to kind of like, you know, bring back all these heirlooms and stuff. But, um, what's happening now is social mobilization is kind of taking off again because climate change has become such like a worry. Um, and now, um, since 2008 in the UK, you are allowed to market and produce heritage seeds again, but you have to be fair certified and you have to have money to be able to pay to be the owner of the seed and kind of the safeguard of the seed. And you have to have lots of space because seeds in order for them to stay alive and in order for them to kind of, um, get used to the climate we live in now and, and the drought or whatever, whatever new pests are in our world now versus back in the 1970s, um, you have to just keep planting them. You know what I mean? Like they can't sit in seed banks because most of the seeds that are currently in seed banks, if they, if they're grown in a soil now, chances of them germinating aren't like, you know, it's not a guarantee.

Dr Rupy: You've got to use them, otherwise they won't, they won't be physically adapted to the current environment that is constantly changing at the moment.

Karen: So that's super interesting because I think even for myself who's massively into food, massively into nutrition, I really lack an education on the importance of soil and the importance of farming mechanisms. So what you're saying is, you know, we've got a system that prioritizes yield at any by any means necessary. And we have, uh, the types of crops that are grown, um, from, yes, a corporate standpoint, but one that isn't adapted to the changing soil environment that doesn't adequately absorb nutrients deep enough from the soil. And therefore becomes more reliant on other chemical pesticides and and herbicides to actually allow them to grow in a in a nutrient depleted.

Dr Rupy: Absolutely. And then what you also have is, so because we've got like a short list of crops that we can grow, um, you are, we, when it comes to harvest and let's say, um, let's say you're farming for the bread industry. So you've got a wheat that's specifically for milling. So you harvest the grain, you send it to the miller, the miller mills it, it sends it off to whatever bakery in Sussex, um, and then I make bread with it. But the only thing about that is I'm baking with just one variety of wheat. Whereas back in the day, like pre-World War I, uh, the way to farm was land races. So land races is basically growing heirloom varieties, um, across your field, um, and there could be like six, seven, 10 varieties, there could be 30 varieties. So you were growing, you know, legumes, you were growing wheat, you were growing barley, you were growing oats, and then all of that was being sent off to the miller, milling it down. So when I made you a loaf of bread, you were eating like loads and loads and loads of stuff there as opposed to just one ingredient. Um, so for me, that, you know, when I started learning about all this, this is what excited me and this is what, um, kind of informed my decision around how I'm going to make bread for people. Um, and, and that's even involving, you know, since I first started Happy Tummy Co. And, and for me, meeting farmers now who are registered with Fair and they're growing heritage varieties, and, and some of them are growing 30 varieties in a field. Um, and, and some of these farmers have sourced, um, seeds that are like 10,000 years, like this guy John Letts, he's a farmer in Oxfordshire, and he went to Egypt and he got these seeds that have been like buried with Tutankhamun. And like, we were at this event the other night and he like showed me the seed, this like black seed and I was like, oh my god, John, that's amazing. And like, everyone's like, my best friend was with me, she's a psychotherapist, she was like, what's going on here? Like, am I missing something? I'm like, mate, like, this is amazing. And like he had it in this little test tube and he was really careful like to mind it all night, you know, because this was precious, like this, you know, we can feel so unconnected with our past, but then when you see this in a test tube and you're like, mate, this is our past and I can ingest our past. Like, how cool is that? And I think, yeah, and I think like a lot of the farmers now that are farming heritage tweets, you know, they are so happy that there are bakers out there like me that are just geeking out on this because, um, you know, bakers that are going to bake this bread for people, you know, when you come into a bakery every morning at 3:00 a.m. in the morning, you're really, really tired. It can be, it can get a little bit monotonous, you know, you're shaping the bread, you're stretching. Um, and you, you want to work with stuff that stimulates you and makes you more interested. And heritage grains, um, do this for you. You know, they, they influence you how you make things, you have to readjust the pH of the water, you have to readjust temperatures, fermentation times. You know, so you're constantly being stimulated. Um, and I feel like being a baker or, or like being any type of food maker or producer is such a wonderful thing to do, you know, forever more. Like you've made your mark on the world in a lovely way, unless you're using lots of pesticide and herbicide. But, uh, you know, if, like, I, I kind of separate makers into like there's those who nourish and there are those who feed. And I've always wanted to nourish. Um, and I think this wave of farmers that's kind of coming to the foreground now, um, are really singing off the same hymn sheet and it's, um, it's a wonderful, wonderful time.

Dr Rupy: And that's a great segue into how you're about to nourish us with some of your bread. I've got a pan here that's on a hot, um, dry heat. Uh, and I know your bread. I've had it many times.

Karen: So this one you have not had.

Dr Rupy: Oh, okay, great. Oh, fab.

Karen: I was like, I'm not going to bring him an old bread.

Dr Rupy: Let me get you a knife.

Karen: Um,

Dr Rupy: So talk us through it.

Karen: Okay, amazing. So, I'll just put these over here. Fantastic. Okay, I'm just going to take this one out of its paper. I don't have a bread knife. Oh, I should have brought one. Don't worry. Um, okay, cool. Tell us about it. So, uh, this is a organic stone ground, um, heritage wheat loaf, which also has got some rye in it. Um, and the reason I've put rye in this loaf is because, um, uh, the farmer who farms this rye, um, just completed a study with the EU, uh, which kind of has indicated that the antioxidant, um, contents of rye are off the scale. Um, and so I guess, yeah, I just want to incorporate a bit of rye into all my recipes now for that reason.

Dr Rupy: Oh, honestly, rye is like one of my favourite ingredients right now. I remember looking up, um, uh, I think it was like last year when I was writing the second book, Eat to Beat Illness, and like you said, it's off the charts in terms of antioxidant profile. There's got some, there's some prebiotics as well that actually have been shown to nurture, um, certain types of microbes in your gut microbiota as well. And, and that's why pumpernickel is like just so, so incredible for you. Um, so I'm so glad you put rye in there. I love the flavour as well.

Karen: Amazing. So in this, uh, all the grain for this bread was grown in Northumberland. Um, quite far north, quite wet. Um, so, uh, the farming of these grains is adapted to the weather, as it should be. Um, so what Andrew, the farmer there has done is he basically plants the grain in November into really, really cold soil. Um, and then he harvests kind of in very late September, early October, which is really, really like different to like how you would farm down in Sussex, for example. So it's really exciting that he has completely adapted his farming to his microclimate. Um, and the grains that are in this bread, the seeds that were used to make this bread, um, he actually sourced from both Austria, um, and the, uh, bread lab in Washington. Um, and the reason being is because, uh, because of.

Dr Rupy: Can I just stop you there? Yeah. Bread lab in Washington. There's a bread lab.

Karen: Yeah, you got to, you got to, you got to visit him. Yeah, you got to visit him. So this guy called Steve Jones, um, is, you know, has this massive seed bank of like really old heritage and ancient wheat varieties and not just wheat, many, many more. Um, and he's doing really exciting things in terms of trying to get people to eat better bread, using all these ancient grains, etc, etc. But it's based in Washington University. Um, and he has worked with Andrew, who is my supplier, um, for many, many, many years, um, maybe over 25, 30 years. Um, and then there was this guy, um, in Austria who was probably like the first guy in Europe, like 30 years ago, to really, really, really start, um, taking kind of old seeds seriously again. And he was, uh, planting all these ancient varieties to now give current farmers who are interested in this way of, um, farming, kind of access to, to things that you can just kind of start planting. Um, so yeah, so, um, Austrian seeds, there's some Russian seed in there as well. There is, um, a hard, uh, spring wheat from Russia in there. Um, and it's just 5% white. So, obviously, in the UK right now, um, 60% of the bread that is eaten is just white. So like, that's just hugely calorific and no really good enzymes or minerals or anything in there.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, it's just stripping everything out of it. The B vitamins and the fibre.

Karen: And like, no wonder you're putting on weight by eating that bread. I mean, and that's why I think bread has a massive branding problem. 100%. Yeah, and this like wheat belly thing. I mean, I think that should be clarified as endosperm wheat belly, you know, like it's not really wheat belly. Um, so, um, this is actually pretty similar, but in this, I've incorporated a seed. So this is an einkorn seed, which is like, yeah, so this is like the first wheat, um, ever planted, really. Um, so that's quite cool. Um, is that the short or I always get confused. Is that the shorter, stumpier one or the longer? Very, very long. Very, very long. Anything ancient and old is like super, super long. Like, it's as tall as us.

Dr Rupy: So the stubbier varieties are the ones that would have survived.

Karen: Those are the modern cultivars. So those are herbicided, pesticided. Like if you walk, if you walk out into the country and you see wheat that is short, that is a modern wheat that was bred to be used for fertilizer. Wheats, all of these grasses should be incredibly long.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, incredible. Because I remember talking, because I did a whole section in my first book about the issues with gluten that people are finding that are not literally related to a gluten intolerance. It's what we've done to gluten-containing products, like pasta and breads and everything else.

Karen: Yeah. And when you like, you know, fertilize a wheat grain, you know, it's kind of like giving a wheat grain crack cocaine or like huge amounts of sugar. It's just like, and the proteins turn out differently. Whereas with ancient old organic varieties, the proteins are so, so long. You know, the proteins that do affect people with celiac disease and gluten intolerance aren't there in any, you know, huge quantities at all. Like they're so small that, you know, if someone comes to me and I'm, I'm gluten intolerant, I'm celiac, I'm like, you know what, try this bread, einkorn wheat, fermented for 48 hours, see how you feel. And they're like, mate, thank you so much. I'm back on the bread. Which is really exciting.

Dr Rupy: That is amazing.

Karen: And how can you live without it?

Dr Rupy: Totally, totally.

Karen: So yeah, so should we cut this one maybe? Yeah, yeah, let's go for that one. I can cut it. You do it. Um, so, um, I use a rye starter to make all my bread. Um, and the reason being is rye starter, uh, when mixed with, uh, flowers and water and all that kind of stuff. Oh sorry, I should have brought a bread knife. You can do another slice. Yeah. Sweet. Yeah, so a rye starter kind of acidifies the flour that it's mixed with completely to create a lot more enzyme activity, which then means, you know, the minerals and vitamins in that grain are more absorbed. So many bakeries and many people, uh, will make like a white sourdough starter or even a cacao one. But for me, I find rye the most interesting, um, in terms of what you get end product wise.

Dr Rupy: Are there any benefits of having like other starters at all or do you?

Karen: Yeah. So you can mix starters. So you could make a bread and use like a white sourdough starter and a rye starter and a cacao starter. And the more starters you use, the more acidification, uh, which, uh, is better for our health. But what I like doing is using a rye starter and like kefir, because the, uh, the bacteria that like the kefir, uh, makes along with the wheat, the grain is very, very interesting and the taste is sensational as well. So, um, for me, it's all about when I approach a new recipe or a bread, for me, I'm starting with like, okay, I want to acidify the loaf completely so that we have complete enzyme activity. We've got loads of minerals and vitamins coming out of there. But I also want it to taste good. I want someone to become addicted to this taste. You know what I mean? Um, so that's really, really important to me that we, we bring nourishment, but we bring flavour as well.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, you need flavour and function. It's like my motto in the kitchen.

Karen: Yeah, 100%. And so yeah, so that's that one. Um, and then, uh, this one I also make with a rye starter. I mean, I need to start using more starters, but you know when you just, when you use the thing that's the best, it's just so hard to. And I think for me now, I'm so consumed by nourishment that it's so difficult to eat something without knowing I'm, I'm not going to absorb the most amount of minerals and vitamins I could. So I think the more you research and the more you study, you know, knowledge just makes you much more functional.

Dr Rupy: Totally, yeah.

Karen: Um, and which is really, really cool as well.

Dr Rupy: Yeah. I mean, it's sort of how I started on my, my personal health journey was through doing a little bit of research and finding out about, you know, the amazing benefits of fibre and different plants in your diet and nuts and seeds and quality fats and all the rest of it. And then once you start small, you kind of build up this repertoire of knowledge. And then the more you learn, the more you talk about it, and then it just kind of grows from there. So I think you, you've clearly like, you're on your way to mastering this art of like health and, um, championing bread and, and seeds and everything. But you must have started quite small.

Karen: Yeah, definitely. And it came out of your own health issues, I think.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, 100%. Like I'm sure a lot of stuff does for people. But essentially, I suppose let's go back. So, um, coming from a horticulturist background, um, I obviously have always had a really, really epic relationship with the soil. Um, so we were a family business, um, and we had to plant thousands and thousands of trees every Easter. Easter was planting season for us. Um, and then throughout the year we would maintain the fields of plants. Um, but when I was maybe 10 years old, my mom got cancer for the first time. And I remember her being in the house, you know, being on the chemo and like all the cancer treatments that you're on. Um, and having this like kind of epiphany, you know, digging some soil out of the earth, putting, putting in another peat sapling and thinking, when I'm older, I'm going to create a brand that's all about preventative medicine. Um, and, and I, you know, you have these like, these thoughts when you're a child and you don't know if they'll ever come true. But the older I got, um, and the, the more my IBS became an issue for me, um, I was like, okay, I feel like I need to go back to that ambition I had when I was a little girl. Um, and when I was younger, my mom ultimately did die of cancer. And, you know, back in the day, you know, when you go to a doctor, they didn't talk about lifestyle medicine. So, you know, my mom was bringing me to these doctors and they were, you know, saying, here's, um, take these laxatives. And I remember my mom every night taking her cancer medication, and she'd do a shot of laxative, and then she'd give me a shot of laxative. And I was like, this is nuts. Like, my mom has cancer, fair enough, she has to take the laxative because of all the medication she's on. But like, what am I doing? Like a 12, 13 year old girl taking laxative. This is nuts. Um, and, and, and I guess intuitively, I always knew food is medicine. Um, so as my IBS got worse and worse and worse into my early 20s, I was like, if I don't sort this out, my colon, something's going to happen. So I really, really, really, really need to start taking this seriously. Um, and I guess, you know, my dad was a maths and science teacher. So science and maths were very much a part of our table chat at dinner time. Um, me and my sister would do like theorems together. So, you know, this, this way of like approaching family meal time was definitely, um, educational. Um, and I guess for me then to just go and study, um, food science myself felt very natural. Um, and then my cousins on the health board of England, so I had her guidance. Um, and then my sister is obviously a doctor, we've loads of doctors in the family. So, you know, there was constantly people to spitball things with, you know, lots of my friends were dieticians and stuff. And I guess I was like, okay, I feel like the world has enough doctors and dieticians and stuff, but what the world doesn't have enough of is like really, really good food producers. Um, so over the course of maybe 18 months, um, I was like buying and studying all the health papers at the time that were coming that were coming out on gut health. Um, and through these science papers, I obviously discovered, you know, uh, the importance of prebiotic fibre, um, how to consume dietary fibre for someone with IBS, how to consume dietary protein, etc, etc. Um, and, uh, basically kind of designed these mathematical equations based on how my gut bacteria liked to eat. Um, and then applied these mathematical equations to recipes, um, specifically bread recipes. Um, and the reason I chose bread was because of the amount of fibre I could get from bread versus a plant-based diet. Of course, bread is a plant-based diet and part of it, but, um, using grains as opposed to like eating loads and loads of broccoli, I knew was going to be kind of the way to really up the amount of fibre I was going to get into my diet. Um, I think a lot of people don't realize that as well, particularly like within the paleo persuasion, you know, they think that you get enough fibre just from having like, you know, your green leafy vegetables and your stems and stuff. In reality, no, you know, you're going to get the most amount from whole grains and nuts and seeds and a good quality bread is a very good carrier of those, uh, fibres, but also the B vitamins within that as well.

Karen: Yeah, big time. And for me as well, like variety was key. So obviously history taught me that like back in the day, we were eating, you know, 10 varieties of wheat in our bread. And now we weren't. So I was like, okay, well, people didn't have the gut issues we have today back then. So let's go back to that. And and a mixture, I guess, of for me, it's really about like the perfect balance between intuition and common sense and science. And I think when you mix the two, balancedly, fairly, you educate yourself, you read enough, I think that's when you, you make food that works for you. But I think if you focus too one way or too the other way, and I'm sure we both know people who go maybe off in their own separate direction a little bit too much, I think that's when fads come to play, gluten-free becomes a thing that everyone's doing, etc, etc. Um, so for me, it was really, really important to, to balance the two ways of approaching food. This looks amazing, by the way.

Dr Rupy: This, I mean, it looks amazing because of your bread.

Karen: Oh no, not at all. I think it's the pomegranate. It really sets everything off. Really good.

Dr Rupy: How was your lunch?

Karen: Very good. Really, really like the barberry.

Dr Rupy: I think the cherry on top was the bread, honestly. Like the team here absolutely loved it. I'm sorry I burnt the second batch, which you won't see on YouTube. But um, if you do want to see the recipe that I made for Karen, um, and the beautiful bread that she brought in, check it out on YouTube, thedoctorskitchen.com, you'll see it there. Um, thank you so much for coming in.

Karen: So pleasure to be here. Pleasure to be here. I'm like tongue twisted after seeing barberry.

Dr Rupy: Barberry.

Karen: Barberry. Yeah, I don't, you know what, I used to be um, a recipe developer for a subscription company many years ago.

Dr Rupy: I didn't know this.

Karen: Yeah. And uh, we used quite a lot of barberry.

Dr Rupy: Okay.

Karen: Yeah, yeah.

Dr Rupy: What did you use it for?

Karen: Um, so we were doing lots of curries, um, and stews. Um, and the whole concept was make a healthy meal in 20 minutes or less. And I think using an ingredient like barberry just brings such a huge amount of, I mean, there must be seven things going on in your mouth. So I feel like it was a good hack to kind of make a meal.

Dr Rupy: I've heard this before. So, um, a friend of mine's a chef and they do, he's got his own sort of like, um, Deliveroo style company, like a dark kitchen and they they deliver it. And he told me that the chef's secret weapon is um, calamansi vinegar. Um, and I guess like even Jamie Oliver's five ingredients, like he required that you had red wine vinegar, I think, as one of the ingredients that is part of the non-five. Yeah, yeah. So and it's because it just adds so much flavour.

Karen: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, just the acidity is so good.

Dr Rupy: Getting the saliva going, the digestive juices, get that enzyme activity going. It's so good.

Karen: Yeah. I actually talked about this with Chef Boulet. Um, the podcast. Yeah, yeah, yeah, loved that. He uh, he's brilliant. He's like just such a wonderful speaker, passionate subject. Yeah. Um, a passionate advocate for the food as medicine movement. He um, he was telling me about the process of in Japan where they have like certain steps before you eat certain things. So everything has a pattern. It's kind of similar I think to the Ayurvedic way of eating. Um, but the the sort of bitter foods always seem to come at the start.

Dr Rupy: And unfortunately, there was an amazing restaurant in Hackney many years ago called Duck Soup, which is now closed and it's been replaced actually by a bakery. So I'm not not that sad. Um, but they um, that was how they they did their meals. So you started with like acidic things, then ferments, then onto the bitter leaves, you know, then onto kind of the like more umami kind of salty foods and then onto the meats and then sweet thing for dessert. But and I loved going there. They had loads of fermented drinks, kombuchas, um, all that kind of stuff, uh, which was quite new vogue like maybe eight years ago. And I was just, yeah, just that and and and the way he talks about it on the podcast with you, you just feel so good after eating in that way. It's just like, yeah, my guts are like so happy right now.

Karen: Yeah, totally. Yeah.

Dr Rupy: Um, so yeah, I'm yeah, I'm a big fan of that way of eating. And also he's like a poet when he speaks. It's just so good.

Karen: He is, he is. The program that he did when he went to Japan, they did three episodes. The ones that I saw were only half an hour. Actually, there was like hours and hours of recordings. And he goes to like Okinawa and he sees all these centenarians and he sees what they're eating. And honestly, the thing that strikes me about it isn't just the ingredients in themselves that are healthy. So the seaweed, um, the organically grown crops and stuff that they have very plainly. It's actually the complexity of the entire diet. Yeah. And I, I think it speaks to what we were talking about about your bread. Um, most people think about bread as like just a few ingredients. But the type of bread that you talk about with such passion is so, so complex with all the different flowers that you use and stuff.

Dr Rupy: And the way to mill. So, um, let's put it into perspective. Yeah. So, well, I'll just hit people with a few facts first just so we really understand what bread is. So, um, 99.8% of British people buy bread. Um, and we consume on average 60 loaves of bread a year per person. That's one loaf of bread a week. Um, 85% of the bread that is made in the UK right now is that kind of sliced packaged bread that we see on a supermarket shelf. Um, which most bakers, um, similar to me would vouch that that's not bread because there's so many stabilizers in there to kind of keep it fresh for two weeks at a time, etc, etc. So that's a different product. Um, and then, uh, 12% of the bread made in the UK right now is, uh, made in an in-store bakery. Um, so we can all probably think of like, you know, every single supermarket across the UK has their own in-store bakery making stuff. Um, and then 3% of bread made in this country is made on the high street in a really, really good bakery where, you know, they respect, um, the use of a sourdough starter, they, you know, use fermentation methods to a degree, whether it be a retarded method or just leave it out for a few hours and then bake it. Um, and within, within those stats, um, 60 to 70% of the bread that's eaten in the UK is white, just white bread. And 50% of the bread eaten in the UK today is a sandwich. Um, so, which is, yeah, yeah. So, um, let's talk about the 3% because those are the people that can really pave the way for bread becoming, uh, part of this preventative medicine way of way of living. So within, um, sourdough bakeries, and I'm sure your listeners can, uh, relate to whatever they have in their neighborhood or have visited one. Um, there is this, um, love for an aesthetically pleasing loaf of bread. Um, and, uh, people and we as customers have come to expect a sourdough to have lots of holes in it, like look quite high. Um, and that will be the case whereby a lot of white flour is present. So white flour obviously contains, um, like all the gluten, the protein. Um, and it will vary in in in the amount based on where it's grown, whether it be, you know, grown in Canada or grown here in Britain. In Britain, we have lower protein amounts in our flour. In Canada, there's much more. Um, and that's why we incorporated, uh, so many Canadian flowers, um, and American flowers into our milling here to to give the bakers what they wanted aesthetically. Um, so we kind of need to pair back how we look at bread and and and start really looking at it for our health and then looking at flavour. Um, so the way, uh, the journey of a loaf of bread is, um, a seed is planted in the ground. Um, and that seed will have been, uh, either bred, um, by a seed bank, um, or a private company, um, to handle lots of herbicide and pesticide, or that seed will be a really, really ancient variety, um, that can be planted organically and can withstand hail, rain and snow very, very well, can withstand lots of weeds growing around it, doesn't need any, any thing from the farmer, bar, plant it, sow it, and then harvest it, come harvest time. Um, so you, you immediately, you, you become a consumer of one or the other. You're going the organic ancient grain route, or you're going like the very, very, very commercial, commercial wheat route. Um, and, and whichever route you go, kind of dictates your health post eating that loaf of bread. Um, so let's first talk about the commercial route. Um, so, um, if I'm a bakery and I really like that aesthetically pleasing, like white fluffy sourdough, I'm probably going to go for that commercial wheat, um, that's, there's been lots of herbicide, lots of pesticide. Um, and then I'm going to mix that with, um, a sourdough starter, uh, to ferment it and, you know, make it healthier and more digestible. Um, so the reason we use a sourdough starter, um, is we want like lots of enzyme activity, we want people to be able to assimilate the minerals and vitamins in that a lot better. Um, and then, you know, we bake it, it's a loaf. You eat that and you know, maybe you've got gluten intolerance, maybe you've got celiac disease, um, and you're like, whoa, I feel really bloated, I feel really nauseous, I feel tired, I feel agitated, you know, my testosterone levels are really high now, I'm putting on weight. Um, and, and that is not surprising because you are, you know, eating a wheat that is not very natural. It hasn't grown in the way it wants. We look at, um, you know, for example, we visit E5 Bakehouse in, um, Hackney, and we go for their wholemeal heritage sourdough loaf. Well, the journey of that is, um, Ben will have sourced his, uh, grain from an incredible producer such as Gilchester in Northumberland. Um, Gilchester have made it their, their, their mission to just grow ancient or heritage varieties of wheat, um, in lots of, you know, mixed populations. So those guys will harvest their wheat, they will mill it on site, which is absolutely amazing because the fresher the better. The fresher the better because more enzyme activity, that activity can kind of decrease, you know, the the further away that comes from, you know, farm to to mill.

Dr Rupy: That makes a lot of sense actually because if as soon as you're exposing the surface area to the air, and it becomes oxidized. Exactly. Yeah. So you're going to reduce that.

Karen: Yeah. So Andrew, the farmer up in Northumberland, founder of Gilchester, is going to send, well, he can actually, he's got two options. He can mill on site and send to Ben in Hackney, or Ben actually has a mill in Hackney. So Ben can take the grain and mill on site and then, you know, make it into a bread straight away. But whatever avenue both those two guys choose, um, let's say Ben wants to make, yeah, a heritage wholemeal loaf. So he will use maybe like an einkorn wheat that's grown in Northumberland. He might mix it with some emmer, he might mix it with like another wholemeal wheat, um, which maybe isn't an ancient grain, but is certainly a heritage wheat. Um, heritage wheats, uh, are like wheats kind of pre the green revolution in which we started using herbicides. Um, and then Ben will mix that flour with a rye whole grain rye sourdough starter. The reason, um, that starters are so incredibly important in bread making is this. When you mix wholemeal flour with water, the aleurone layer, which contains the phosphorus, um, and like lots of vitamins and minerals, um, that reacts with the pH of the water to start, um, kind of absorbing all the iron and zinc from the grain. So phosphorus, it's stored for form phytate, is negatively charged. Iron, zinc, calcium, magnesium, all these incredible nutrients and minerals, they are positively charged. Um, so the reason, uh, intuitively back in the day we knew to make a sourdough starter was when you mix your sourdough starter with water, you reduce the pH of the water, thereby, uh, reducing this kind of phytic acid response. Um, and that, that is the crux of kind of the whole bread making thing, right? So, uh, you want to know your bakery, you want to know where your flour is coming, you want to know that they're using sourdough starters that completely acidify, um, the wholemeal flour so that you get all the vitamins and minerals, all those B vitamins, all those E vitamins, etc. Um, so, um, and whereby the milling, to answer your question properly, really comes into play is there's two ways of milling. So there's the modern way and there's the old way. The old way of milling flour is stone ground, so creating lots of friction, um, which is awesome and kind of breaking down the brand structure. Uh, the second way, the modern way is using big like kind of two meter long roller mills that are so hot, they can kill a lot of the enzyme activity that should happen in the grain. Um, and that's why I tell all my bakery students and everyone that will listen to me to always buy stone ground flour because the less enzyme activity you have going on, you know, the less able the grain is to break down itself into vitamins and minerals that feed us and reduce inflammation around our body. So how we mill things is one part of the equation and it is an incredibly important part of the equation.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, that's fascinating because I, I see parallels between how you treat the raw ingredient of oils and how you create oils with, with how you make bread now. Um, because if you take, uh, the nuts or the seeds to a high temperature, you're actually destroying a lot of the phytonutrients in oils themselves. The heat extraction method and chemical extraction methods can be quite harmful as well. Um, and can be inflammatory and there are some studies that have shown that. Um, and also you, you get left with a less palatable product. Yes. And I think there's so many parallels with that with bread making because I, I wouldn't have thought about the enzymatic activity of the actual grain, but now it makes perfect sense.

Karen: Yeah. And I think this equation of everything coming together so, so beautifully is so, so crucial. And I think, you know, understanding that we have to reduce the pH of water to enable the grain to not kind of spontaneously combust on you almost. You know what I mean? Like there, there. So in the world today, the World Health Organization has identified that across the world, we are deficient in iron and zinc, even though we're eating more cereals than ever before. So 20% of our daily calorie intake across the world on average comes from wheat. But how can we absorb iron and zinc when we don't use a sourdough starter to reduce that pH, enabling phosphorus to just like go off and do its thing and allow all those other vitamins and minerals present to eventually, you know, go into our body and allow us to kind of absorb them and, and, and yeah, do what they're meant to do for our health.

Dr Rupy: That's such a good point because the same sort of conclusion was reached by, uh, the researchers, I think it was published in the Lancet where they looked at, uh, consumption rates of foods over the last, uh, I think it was 20, 30 years. The headline was, our diet is killing us. What really was going on is that we're not eating enough whole grains, nuts and seeds and legumes. And that's actually where you get a lot of iron and zinc from, as well as some animal products. But I guess if the food system is failing us, then how do you expect people, even if they are going for the whole grain bread in their supermarket, to actually attain the levels that will be conducive with healthy outcomes?

Karen: Yeah, absolutely. And because, um, government and stuff is so aware of this now, what is happening is a lot of white flowers are, um, you know, being, uh, what's the word for it? Basically, we're adding calcium, we're adding things to our white flower. We're fortifying it. We're fortifying our cereals massively, more than we, I mean, we've we never fortified cereals pre World War II. Um, and, and, and therein, I guess, lies the problem. You know, as a, as a race, we've kind of become lazy to what we need to do to make our food sit well with us. Yeah. Um, and give us the life that we want to live, which assuming for everyone is a healthy one. Absolutely. Um, and I think, I'm so, so passionate about eating organically as well. And I think it's one thing to say eat whole grains and it's one thing to say, you know, eat more plants, etc, etc. But if you're doing that and the food you're eating is so sprayed with pesticide and herbicide, you are not eating a natural food. You are eating a food cooked up on some sort of like weird chemical stuff that like you're it's completely foreign to your body. I mean, it just blows my mind, you know what I mean? Like it blows my mind. And you know, we're here sat in January and a lot of people are doing, um, a vegan month, um, which is cool, but are organic sales increasing this month in conjunction with that? Plant sales are going up for sure, but with that herbicide goes up, pesticide goes up. Um, and what blows my mind is the amount of times that the food we eat gets sprayed like a season. So for example, in wine making, which is very, very similar to grain making, um, a vineyard in Australia or France could be spraying their vineyard up to 16 times a season, which is nuts. So like instead of having, you know, pre World War II, like loads of varieties of grain in your diet. Now you've got loads of variety of herbicide and pesticide. And I feel like it it sometimes it can be, um, uh, not very politically correct to, you know, go so, so hard on this like organic way of eating because people are like, it's elitist, you're privileged to be able to buy organic food, etc, etc. But, um, when I was running the bakery in Hackney, we had loads of customers that were on the bread line that were buying our bread because they fundamentally understood the importance of organic whole grain food in their diet. And those were the people as well that understood, you know, the lifelong impact that one way of eating was having on the planet versus another.

Dr Rupy: Let's go back to that. So we talked a little bit earlier about how, um, our agricultural system has, uh, changed a lot since World War II because what we were doing is prioritizing yield at any cost. So just trying to get as much food as possible to, uh, uh, feed the population. So it's more and more monocultures. But then also that combined with the types of, um, uh, agricultural practices led us to be more reliant on things like herbicides and pesticides. And also there's a sort of like, uh, commercial corporate aspect as well where if there are a handful of companies that hold the patents over seeds or the the lock and key over seeds so to speak, um, then they essentially control a lot of what is produced and then and this leads to these sorts of practices.

Karen: Absolutely. So the way the world works currently, um, and and we are in a changing time, fortunately, but still currently, there are seed banks around the world and as you said, there are owners of seeds with patents of certain seeds. Um, and the more global we became, obviously, the the more commoditized food became. Um, and governments saw fit to, um, make everything a bit more like linear and make everything a bit more uniform because that meant trade was easier. Um, and everything had a certificate to kind of allow it to be traded. Um, and there are huge benefits to that, of course. There are huge benefits to certification, um, of food. But what happened was certifying these seeds is a really, really expensive game. Um, and through the legislation of, um, seeds and seed banks, etc, we kind of overnight stopped growing thousands and thousands and thousands of varieties. So, um, eventually what kind of used to be a very government-led job, you know, seed protection, soil protection, became one of global interest. Um, and unfortunately, we live in a world where, uh, big corporate companies work side by side with government in terms of advising them, you know, it's it's a it's a very, um, they share a lot of knowledge with one another.

Dr Rupy: It's quite insidious, isn't it?

Karen: Absolutely. Um, so kind of very, very, very quickly over the course of a few years, um, 60% of the world's seed trade, uh, just was bought up by kind of four main companies. Um, and those companies are incentivized by by profit margins. Um, and they got very, very, very, um, stiff on making sure that everything was legislated, like everything, everything, everything had to go through. So for example, um, if I'm a farmer in Suffolk, um, and I want to grow a new type of wheat, I need to go through a 10-year kind of period of where I need to prove that this wheat is going to drive more yield than the wheats currently on this national list. Um, and I also have to pay 100,000 pounds. So we have people trying to get into a food system who have no money, but are very well-intentioned. Um, but they will never be able to get their hands on 100,000 pounds, never mind the land needed to prove point this wheat is better than wheat currently on said national list.

Dr Rupy: What's the, what's the actual reason as to why that is still the case now?

Karen: Um, so, um, because of like where it legally is at. So, um, so, um, it's essentially, I mean, the government could do a lot about it. So, um, the government have said, this is the national list, these are all the wheats that are allowed on it. Um, and if you're not on, if you want to farm a seed that's not on this list, well, I mean, tough luck. Or go away, buy some seeds from a seed bank that you do actually want to grow and maybe bring back into, um, plantation. Um, and, and, and tell me, check out if they're going to be better than these seeds or not. Um, so a farmer could spend 10 years, uh, you know, with a whole hundreds and hundreds of seeds from the seed bank, hoping that some of them are going to germinate and hoping some of them will have more yield than the other ones. And, and it might just all, you know, fall on deaf ears. So, um,

Dr Rupy: So we're not incentivizing entrepreneurial spirit within the farming industry.

Karen: Absolutely not. Um, so back in 2002, you could only grow a wheat that was on this national list. Um, but in 2008, due to social mobilization, um, across the world, particularly in South America, um, where like peasant farmers continued, even though the legislation said whatever it said, they continued to just grow and keep all these, um, heirloom varieties alive. Um, through that and and and also through kind of, I guess, more so than anything, the bakery industry and the bakers within that industry wanting more from the grains that they were using, wanting more flavour, wanting more nutrition. Um, from this kind of movement towards food as taste and nourishment again, came this, I guess, resurgence of farmers who are entrepreneurial, who were maybe already organically farming, but now wanted to kind of up that by, you know, bringing ancient varieties back into our system, etc, etc. So in 2008, um, the government said, okay, um, as a conservation kind of mechanism, you can now start growing these heritage varieties again, but you have to be registered with us. This seed has to have an owner. Now you're the owner of it, you have to pay a subscription fee, you know, every year that to keep that that going. Um, so you know, there's still lots of strings, like there's still a lot of work that one has to put in to, um, bring more diversity to our soil microbiomes health again. Um, and I mean, that's quite sad, but I guess on the other hand, we are lucky that there are farmers out there, uh, entrepreneurial enough to be able to get investment, to be able to get loans from the bank, to be able to get grants from universities and work alongside universities. I think Gilchester is a really good example of a farmer who went and did a PhD with Newcastle University, um, and and really engaged them and through the relationship with that university, you know, that opened up, you know, conversations with Washington State University and, you know, people in Switzerland and Austria and stuff like that. So on one hand, the global stage and and the global players have actually enabled Britain to kind of start refarming these heritage grains, but on the flip side of that, globalization has put us into this mess in the first place. Um, and I guess, you know, pre, pre kind of the 1900s, it was, it was crop husbandry is a wonderful way of talking about it. So, you know, a farmer would just figure out over time the seeds that suited his microclimate and his soil. And you, and that was the way it was. But post World War II, what we did was, let's make, uh, let's make the soil suit the plant. Or let's not even really think about the soil. Like, let's just create some products to make these like 20 crops work across Europe, which is just like so, so crazy.

Dr Rupy: It is insane. It's kind of like forcing the entire population to eat a certain way, a certain macronutrient composition, a certain cuisine. It's just saying, this is what we're doing now. This is optimal for health or whatever for the majority of people. So everyone's going to do it without any consideration of intervariability. And the soil, and this is a lovely segue into the soil because I think not enough people care about the soil. And the importance of the soil's diversity and microbiome.

Karen: And I mean, your food is reconstituted soil. Exactly. Like I remember growing up, um, doing lots of planting and and fortunately, I feel so blessed to have had this way of living. I was so aware that the heads of lettuce I then ate were just whatever was in the soil. And I never washed my lettuce when I was growing up. Like I never washed my food because I was so obsessed with soil. I mean, anyone that's a bakery student of mine, I do wash the lettuce I serve in my bakery school. Um, just because obviously I don't want anything bad to happen. But I mean, my choice is that I don't, you know what I mean? So I think that's a lovely way of putting it. If if you can reflect on just that one line, if that's your one takeaway from this podcast, that your your food is reconstituted soil, then I think everything just starts to kind of fit in.

Dr Rupy: It starts making sense, isn't it? You kind of see the cycle of life, the food life, the animal life, everything. It all has to be with a a nutrient dense soil. And how have we got to this, this is an education for me as well because I don't think traditionally I've thought too much about farming practices and soil. And this is why I wanted to you to come on the podcast because not only do you know so much about it, but you're you're also not afraid to talk about subject matters that are politically incorrect. Whenever I mention the subject of organic, I always get shut down because I'm, you know, thought to be elitist or whatever. But actually, I think it's a very important conversation to have.

Karen: So important.

Dr Rupy: And we can't have hang ups about these things. And I think we need to, it's something I wrote about in my first book. We have the opportunity to change the future food landscape for generations to come. And yes, there are going to be arguments against organic farming in the short term, but long term, what do we want to create? A population that is, uh, healthy, thriving and, and is, is nourished by a good performing soil.

Karen: Just reliant on good food versus pharmaceutical products.

Dr Rupy: 100%. Exactly. That is the best form of preventative medicine. And it starts in our soil. So there are a few organizations that I think are championing this. But in terms of the way I think about soil, I think the reason why we've seen a lot of degradation of the mineral concentration and the biome of the soil, so the actual living, because soil, we think of as dirt, it's not dirt. It's it's a living, breathing entity with microbes and bacteria and everything, fungi. Um, but the the way I think about why it's been degraded is two things, two main things anyway, and correct me if I'm wrong if I've left anything out. Monoculture and overuse of herbicides and pesticides.

Karen: Absolutely. So, um, obviously there are many ways of, um, approaching monoculture. Um, and some farms, uh, depending on their microclimate, the best thing to do there will just be to rotate animals. Um, you know, have sheep one week, have cows the next, have goats the next. Um, and there's just turds everywhere. Um, and then the second way is using, you know, compost materials, you know, food waste, seaweed obviously is a brilliant one. Um, and, and maybe some amount of animal turd. But, um, certainly that is again kind of a part of like crop husbandry. The farmer, so there's a farm, there's sheep drove farm in Hampshire. Um, and they are, they they heavily rotate their animals because they have found that that has given the soil in that part of the world a huge amount of nourishment and has then enabled them to grow a very, very good variety of ancient grain. But in Suffolk, where there's more sunlight and more photosynthesis and stuff like that, they have maybe found that it's actually much better just to use like vegetable like, you know, composition and seaweed and stuff like that. Um, so and and this is where actually I see people being elitist. Um, as, so let's say you are, um, a vegan, but you don't eat organic, but you have lots of problems with people eating animals. Okay, that's fair enough. You're completely entitled to that. But are you entitled to attack farmers for what they do when you know that's a difficult job? So part of like the skill and the intuition and the science around being a farmer is to live with that farm for maybe 70 years and discover what is best to drive the most like health and nourishment into the soil. And for me, that is the most respectable job in the world to be able to do that and commit to that over a lifetime is so, so, so incredible. And it's fundamental to our health. So, you know, if you think, you know, eating animals is not good for your health, okay, fine. But like, actually, let's look at the facts here. Like, let's look at the facts of soil health. Farming has to exist. If anything, I think it's the one industry that needs to grow bigger, but with definitely a bit more legislation around, you know, being organic, being more natural, not spraying as much, etc, etc. I think we need to become much more local in terms of how we look at farming. And I think we can't really discuss farming as a whole anymore because it's so microclimate based. Um, and I think for, you know, governments in America to infiltrate the Venezuelan government and how they do things or, you know, us to infiltrate like Ethiopia's government, that is just wrong. We need to, obviously globally come together and say, hey, we're going to just do better for our soil. But now let's let it up to like governments and social groups within those countries to, um, not dictate, but certainly kind of get behind one another, um, and, and, and grow better and, you know, walk on our soil better.

Dr Rupy: What would you say to the criticisms that people would have about the importance of yield and how if we go to a more natural organic way of farming, that the produce that would be able to, uh, produce would just be so minimal or not to the, uh, amounts that we need in, in today's day and age?

Karen: So, um, firstly, I, I, I think it's definitely a concern that we need to be very mindful that we, we create enough food in this world to feed a growing population of people. So we think that by 2050, we'll have 10 billion people in the world. Um, and, um, most of those numbers are actually going to grow in places like Africa and South America. Um, so yes, it is so, so, so crucial to not be misguided by nourishment and kind of forget about yield. But what has been proven time and time again is that the more variety in our soils, the more robust our crops are to microclimates. Um, and I think that's why we need to kind of say, uh, I mean, World War II was not anything to do with the soil. World War II was people killing people. That was like a political, that was a horrendous time in political history. But that had nothing to do with agriculture or horticulture. So because people killed each other, um, and because people were starving and like farms were just trodden, vineyards across the world, like, you know, land was destroyed. Um, we obviously had to concern ourselves with yield. But now, if we can, if, if politically we can lead ourselves safely and fairly, and if we can, uh, continue to, you know, yearn for a politically stable, uh, globe, then farming has nothing to worry about because then we are focused on, you know, micro community, you know, growing ancient varieties that can withstand drought. Um, and the ones that can't, it's okay because we grow them amongst the ones that can. And through open pollination, you know, the ancestors of those ancient grains are more and more and more robust to pests, to drought, to a whole range of things. So I think we need to make sure that we, you know, discuss food and not get so kind of, uh, not forget about what politically happens and what politically actually impacts our food.

Dr Rupy: Yeah. Do you think the Eat Lancet Commission went far enough when it came to trying to, uh, hypothetically consider what would be the ideal diet for most people? Because it's quite heavily plant-based. And I think it's been attacked from both sides. Vegans saying, well, it's not plant-based enough. And, uh, those who are perhaps more of your persuasion from a farming perspective are saying, actually, healthy soils to breed healthy plants need healthy animals. And we do need a lot more ruminants than's actually suggested in this plate. And if people, if everyone was to stop eating animals tomorrow, would we actually have the diversity that you're talking about in the soils? Or maybe there is a path where you can actually do it with just plants.

Karen: So I think again, unfortunately, it is, it it's just so, I I I've almost become tired of talking about subjects on a global level because it is just so micro. And and like I was saying to you, like sheep drove, if they didn't have a lot of animal composition going back into the soil, vegetarian composition cannot give their soil the nourishment it needs. Like there is in Suffolk and and similarly in Northumberland, um, they actually favour a 50-50 mix of the two. They favour vegetable composition as well as animal composition. Um, but I, you know, I think people still really love to eat meat. I love to eat meat. I don't eat a lot of it. Um, and actually this year I've promised myself that the meat I eat, I will kill myself. So I think, you know, the more knowledge you acquire, like we were saying earlier, you know, it, it more plays on how you function. And I've seen the vegan argument, I've seen all these, I've seen these arguments from people, and I really respect them. I respect them so, so much. I respect the, the animal movement so, so, so much. But on the flip side, to sit at your kitchen table and eat an inflated chicken breast, like that, I've got a problem with that too. A huge problem with that. You know, like, you know, nitpicking bits off animals, not respecting kind of this nose to tail culture that Fergus Henderson kind of really spearheaded in London 30 years ago. I think, I think we are still not consciously eating.

Dr Rupy: Yeah. And I think consciously eating is something a lot more of us need to do. I'm quite proactive in that. Not only do you need to get closer to the soil and the vegetables and the plants that you're eating and actually learn how to cook them and prepare them, etc. But also, if you choose to eat meat for whatever reason, for health reasons or otherwise, um, you need to understand the process that this has happened. This reminds me of the story, I always come back to it, um, when I shot my, my own bird for the first time. It was pheasant, and I shot it and I remember holding it in my hands and it was like lifeless. And I remember thinking about it. It was a a sad situation, but it made me understand and it brought me so much closer to the food that I was eating. And since then, I've always thought very consciously about the type of food that I'm eating and also like where it's come from, the journey it's been on. Um, and it was like one of the most life-changing meals that I made for myself because I plucked it, I gutted it, I prepared it. It was a lovely like, uh, ale and a whole bunch of other veggies in this bake that I made. Um, but, uh, since then, I I've learned a lot more about the whole process about actually how animals are farmed.

Karen: And that's survival, right? That's survival in a really respectful way. Survival in a non-respectful way is building loads of factories to kill hundreds of chickens at a time from some, you know, weird gas chamber or whatever the case may be. But what is respectful to our environment, to ourselves and to animals is to kill them really, really, really quickly. They've had a good life in the wild. Like we are all animals. And I mean, if someone were to kill me, I would prefer a shotgun to the head than, you know, than like go into a chamber like Hitler style and like, you know, that is how we are treating animals. So like I said, I appreciate and respect the vegan movement so, so, so much. But, you know, I think we all have to maybe go a little bit deeper in our research of things and self-education before we maybe say something disrespectful to someone who's actually farming in a very sustainable way, who maybe himself is a vegan. Yeah. Um, and I think, you know, animals and a variety of animals have to exist to keep this planet safe and healthy. For example, there's um, a rewilding project after starting in Suffolk. Um, and this month they're introducing six beavers onto the rewilding estate to help with drought, um, and flooding and all these kind of cool things. So like in Britain right now, what's super exciting is we're actually trying to introduce more animals into our ecosystem and that's super, super exciting.

Dr Rupy: Yeah. That's super, yeah. And I I think just to come back to one of your points earlier about how it's quite tough to talk about things like this on a global scale because like you said, we live in microenvironments, whether we like it or not. And actually what works for someone here in the UK might not be relevant for someone who's living in South America or a part of Africa or a part of India or Indonesia.

Karen: I had a student from Madagascar come to one of my classes a few months ago, beautiful girl. She's a student here, a science student. And she came and uh, you know, the day goes on and people kind of unfold their layers a bit more. And she was like, Karen, when I came to this country, I started doing weights. And like, I was sitting in an awful weird such back pain. I was crippled. You know, I changed my diet completely. You know, I just got so consumed by the information from some of these influencers I was listening to. And my mom got really worried about me. And it took my mom about six months to kind of take me off this rush, this addiction I had come accustomed to, which was doing weights every day, you know, eating a diet she wasn't accustomed to. And and she, she, she walked every day in Madagascar. You know, eating what made her feel happy and nourished. And she's an intelligent girl. She's doing a science degree. You know, she, she knows her stuff. She, she knows what chemistry is. You know, like, and and that's why we need to look at things in a microclimate way as well. Because not only is it our soil, but it's also our mental health. And like how one girl can infiltrate another girl's mind to change her for the better, inverted commas? No. I think and I think that's one of the amazing things about teaching people and baking people is like, I go on the journey with them. So maybe like seven years ago, I didn't really understand what a 34-year-old woman was saying to me. And now I'm like, I want to ring her and be like, hey, I get you now. Like, I'm there. So I feel like with age as well and the more you meet people and, you know, I'm so, I just feel like you're so lucky to meet so many people every day and I mean, it's so tiring and it's exhausting and everything, but your approach to it and your approach to then being able to change someone's life with like such balanced attitude is, is, is incredible. And I think unless you can approach someone in what you think to be fairly, then maybe just don't say anything. You know, like maybe, maybe, um, Rita comes to you and she's like, you know what, Sarah, I'm feeling really bloated, like I don't know what's going on. Maybe don't say to her, why don't you consider coming off gluten? Maybe gluten's your thing. Maybe say, you know, God, that sounds, that sounds awful, really. I mean, you know, maybe go see a therapist, go see a doctor, you know, let's chat or reach out to your sister or whatever it is. You know, maybe give her some advice that enables her to make her own decision for her own health as opposed to inflicting your belief system on her. And I think that's something I've become even more conscious of now. So when students come to my bakery and they say, you know what, I don't actually eat a lot of bread, but I'm doing this, but I might eat just, you know, make it once a week and that's fine for me. And I'm like, that's cool. You know what I mean? I'm like, in my head, I'm like, oh my god, why don't you eat this every day? But that's not fair. Like, cool, like you're going to have porridge one day, you're going to. I'm like, mate, your gut health is probably way better than mine because you've way more variety. I'm so obsessed with bread. So I think like, yeah, I think I've just, to put a long story short, just become so bored of the global argument. I just, I, because I can't make sense of it. And if I can't make sense of it, I get disengaged and I get a little bit angry at the people who are, you know, still fighting that fight and aren't trying to actually make a difference in their community.

Dr Rupy: I think, uh, and it's something we were talking about a little bit earlier where it's the collective actions, the collective small actions of a small group of people that actually will have an impact on local communities. And you're a passionate believer that you're going to revolutionize, you know, the farming industry and and actually how we do things from a soil perspective by doing the small activities that you're doing that are going to obviously grow into a much bigger movement.