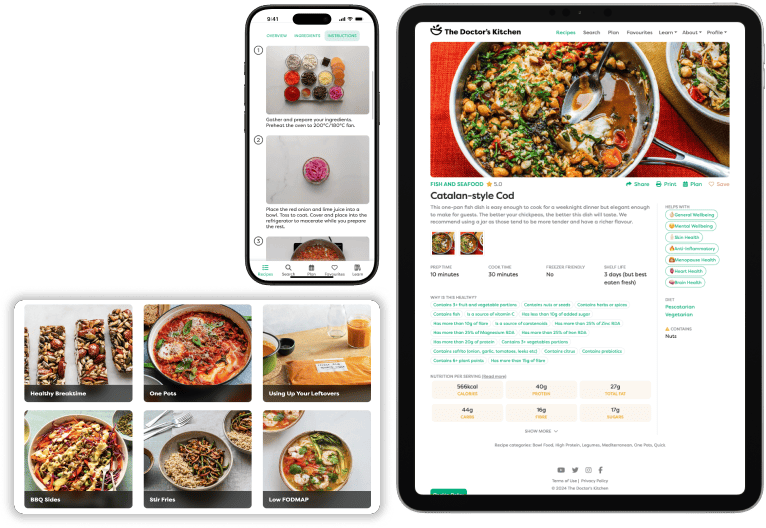

Dr Rupy: Recipes, health, lifestyle.

Dame Sally Davies: COVID is the lobster dropped into boiling water and it makes a lot of noise. AMR is the lobster put into cold water and heated up very slowly. It doesn't make any noise and the RSPCA say it's much kinder, but it'll be dead all the same at the end of the day.

Dr Rupy: Welcome to the Doctor's Kitchen podcast. The show about food, lifestyle, medicine and how to improve your health today. I'm Dr Rupy, your host. I'm a medical doctor, I study nutrition and I'm a firm believer in the power of food and lifestyle as medicine. Join me and my expert guests while we discuss the multiple determinants of what allows you to lead your best life. How much do you worry about a simple cut? Humour me for a moment. Let's say you have a momentary lapse of concentration when you're chopping up your onions doing one of my recipes and you open up a small wound in your finger. After a couple of days, you realise it's not getting better despite washing it with water and you do the right thing and you seek attention. You see me in hospital and it's getting red, hot and swollen and I tell you it's probably infected and we need to start some antibiotics. Now, think about another scenario where everything just like I said happens, but instead of me starting you on antibiotics, I say we need to keep this clean, we need to make sure that it's sterilised as much as possible and pray that it doesn't become infected because otherwise it could become septic and you could become very sick. We don't have any drugs to treat it. Now, this was the situation before we had antibiotics and unfortunately, it is looking like we may be facing the same situation because of antimicrobial resistance. This is where the drugs that we have developed do not work because microbes have developed resistance via a number of complicated mechanisms such that our drugs do not work. This is a scary, frightening scenario that is staring at us right in the face if we don't do something about it in the next couple of decades. Today to talk about this frightening situation is Professor Dame Sally Davies. She is an eternal optimist and I'm so glad we're going to be talking to her on the podcast because she is the perfect person to be talking about this very situation. She was the Chief Medical Officer for England and senior medical advisor to the UK government between 2011 and 2019 and recently, just at the end of 2019, she was appointed as the UK government's special envoy on antimicrobial resistance. She's also the 40th Master of Trinity College, Cambridge University. And in 2020, during the New Year's Honours, Dame Sally became only the second woman and the first outside the Royal family to be appointed Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath. It's an incredible achievement and she is just a pioneer in so many ways as you will hear on the podcast today when we talk initially about her career in medicine. Now just to set the scene before we define microbes and explain what resistance is and what the mechanisms are before microbes become insensitive to antimicrobials, I just want to paint the gloomy picture of how 10 million people worldwide will die every year by 2050 unless we get the antimicrobial resistance problem under control. It would cost in excess of 2% of the global GDP. That is trillions of dollars in killing more people than cancer. And currently, it's almost a million people per year that die because of antimicrobial resistance. That is more than COVID right now. It's also been predicted by the founder of penicillin, Sir Alexander Fleming, in his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize. So this is an issue that we have known about for decades. Yet, as you'll hear on the podcast, there isn't much being done about it, or there hasn't been up to this point because of a number of different issues. Now, a lot of things are moving parts in this. It's not just about the agricultural industry, it's not just about overuse of antimicrobials by consumers, patients, of which we all are, but there are multiple players involved in this and it's going to take a hugely coordinated effort just like we're seeing with the pandemic right now. I hope we end with a positive note and I'm definitely going to be talking about this subject a lot more over the next year. And if you want to listen to some of the incredible lectures that Dame Sally Davies has given, as well as other people, I've put a whole host of these resources on the doctorskitchen.com/podcast page, so do check that out as well. But for now, enjoy my conversation with Dame Sally Davies. Before we go into the core topic of what you're on here to talk about today, which is antimicrobial resistance and preventing future pandemics, I'd love for you to regale your story of how you got into medicine and what led you to medicine in the first place and your various positions throughout government since then.

Dame Sally Davies: The potted version. I wanted to do medicine because I was given The Double Helix by Watson by my mother when I was a teenager and I thought it was beautiful. And I've kept my interest in genomics and gene disorders ever since. I probably sounded a bit silly in the medical school interviews when they said, why do you want to do medicine? Well, the double helix, it's so beautiful. So I was, that was what drew me in. And I would say that I enjoyed medical school, but I actually enjoyed it not because of medicine. I hated anatomy and the smell and other things, but because I enjoyed being at university. But then I found the first year very brutalising. I found it very difficult. We were at a time of the NHS when rationing was obvious and accepted and I found it painful when people didn't get what clinically they needed. I didn't like that. So after a couple of years, I opted out and became a diplomat's wife. That was interesting in itself. I'm clearly not happy as an appendage, but I learned a lot. I learned a lot about the civil service, the hierarchical system, but particularly the power of talking to people and the written word and framing things. And I thought this, I didn't know I was learning and I didn't know it would be useful, but everything comes in useful later on. I came back into medicine and actually divorced that husband and remarried, and decided to go for paediatrics, but it was too general for me and I ended up doing sickle cell disease throughout the ages, having done paediatric membership. And I looked after three generations of some people with sickle in Brent and they're the most wonderful population to look after and very special people. And I admire how they live with the pain and the problems and everything. And then I was drawn into NHS research and development by being rung up and asked if I'd serve on a research committee. And the story told of me by the secretary of that committee is I said nothing for a year while I learned the business. The second year I started talking, the third year I took command and the fourth year I chaired it. I think that's a bit excessive, but I do believe in learning the subject before I opine and watching how the system works. And then I was headhunted to become the director of research and development for the NHS region. And with every new NHS reorganisation, I was given the bigger job, which was always very funny. I remember going to see Nigel Crisp and saying, well, you've got two contenders for the R&D directorship of the London region. Both of us are competent, so choose the one that'll make your team work and it's fine by me if it's not me. My colleague was not pleased it was me. And eventually I got to the point where I was the deputy to the Director General for R&D and I had to decide would I apply to take it on and he encouraged me. And I looked at the people who were running for it, all men, and I thought, we need a change, we need a shakeup. So I went for it, got it. Thank you to that interviewing committee. Again, Nigel Crisp, but also David King, for instance. And then I set about reforming R&D in the NHS. And there were so many battles, not with the politicians who thought I was onto a good thing, nor the civil servants who said, oh, go for it, but with the academics who thought that I was going to put lots of money in my back pocket and give it away to the NHS and it would all be lost and wasted. And actually, I conceived and set up with my team the National Institute for Health Research. By the time I'd run it for 10 years, we had gone from 500 million sunk in NHS hospitals, taken out and put back transparently for research and added to it so that the budget was one and a quarter billion that I handed over to my successor. So far from pocketing it, I more than doubled it, which I'm not sure is going to happen again. And then in 2010, I was asked to locum, I suppose you'd call it, as Chief Medical Officer. I was the interim Chief Medical Officer. And when it came to applying, I discussed it with my husband and he said, well, don't you want to be the first? And I said, I don't know. And he said, yeah, but you don't want to answer to someone you don't respect. One of my problems through life is I'm not very good with people I don't respect. So I went for it and I did it for nine and a half years and finished September 31st last year, 2019, to start here as Master of Trinity College, the first woman again. And on October the 1st. And so I'm now just starting my second year. I thought it was going to be peaceful, but then COVID came.

Dr Rupy: There's so many firsts there. You're truly a pioneer when it comes to all aspects of your career. One thing I do want to touch on actually, and this is more for my personal interest is, how you dealt with moving from frontline clinical duties to the more academic side of things that you've been doing over the last 10 years plus.

Dame Sally Davies: So I miss the patients and in fact some of my patients still email me and I'm in contact. Doing sickle cell disease means you're a specialist, but you also have that advantage of a GP that you see generations and you see them grow up and it's lovely seeing that. So it was a wrench, but I felt I could do more good if I went into this role. And actually, after a year in R&D as the director of R&D for the region, I went to my then boss and said, the skills that got me this job are not the skills I need for it. So, I burn out, I refuse, I leave, I'm happy to, or you pay to train me. And he said, well, that's a no brainer. I'll pay to train you. And I went to the European Business School, INSEAD at Fontainebleau for a course on emotional intelligence and leadership. And it had a massive impact, not only on work, but actually on home as well. It was life changing, fascinating.

Dr Rupy: That's incredible. Yeah, yeah. I had no idea you went to INSEAD. That's amazing.

Dame Sally Davies: It was a three week course, a week on, six off, a week on, six off, a week on. And the first week was kind of taking each of the 21 people apart, 20 men and me, 20 private sector and me. The second week was rebuilding them and the third week was existential. And it was fascinating and yeah, absolutely changed how I go about things. So there you are. We have to learn and we have to develop all the way. And here I am at Trinity, learning and changing as I go.

Dr Rupy: Brilliant. All right, well, we could definitely talk about your career thus far for another hour, but why don't we get to the core topic of what you're dedicating your work to now and where you started, which is infectious disease and antimicrobial resistance. Where was the first, when was the first time you realised that this is a huge problem? Has it, has you always realised that throughout your whole career or was there a tipping point at some point?

Dame Sally Davies: Well, of course, like any doctor, it happens to you, it happens to the audience. We've had patients who had a resistant bacteria, but in my generation, there was always another antibiotic. And then I came as Chief Medical Officer to writing my independent annual reports. And I thought I'd start with something non-contentious, infection, community, acute care, tertiary care, non-contentious. And I do it a different way from my predecessors. I'd get in the experts, they'd write chapters and my role was to choose the subject, choose the right people and write what does this mean for policy. So they all came back when they'd written their chapters and we were going through, so what did it mean for policy? And kind of halfway through, I said, oh, shit, you mean this has got really bad now? And they said, yeah. And I said, so what are you doing about it? So they said, well, we keep telling people. And I said, yes, but what are you really doing? And it turned out that they hadn't managed to get people to listen to them. So the experts were not being heard. I'm sure if they were surgeons or transplant docs or cancer docs, they would have been listened to. But they weren't because they were microbiologists and ID doctors. They'll have their heyday following COVID again, won't they? Thankfully. But I so I decided to give them voice and I started and over the years I've acquired quite a lot of expertise in it, but it wasn't that I intended to do it, nor that I knew a lot at the beginning, just, hey, this matters. If we don't pick it up, who's going to? And Britain's played a leadership role in this across the world, which is massive.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, stemming back to Alexander Fleming's time and the discovery of penicillin. I think why don't we take a few steps back and actually define for the audience what we mean by microbes and bacteria and how that differs across the different microbial species, what resistance actually means and how long we've known about this issue and you picked it up during your first report as CMO. And later on we can talk a bit about avoiding the environment that promotes antimicrobial resistance and preventing widespread issues that that entails.

Dame Sally Davies: Okay, so we're going to do the works. So, surrounding us, in us and on us are infectious organisms. They're bacteria, they're viruses, they're fungi, parasites. Indeed, in us and on us personally, we have more infectious microbes, I'll call them, than we have human cells. We call it the microbiome. It lines our gut, it's in our ears, on our skin, in our mouths. Most of the time, they're good for us and they look after us. But some of them can be pathological and harm us, whether they're viruses, think of HIV or COVID, whether they're bacteria, think about E. coli. And of course, what happens is if you get an infection, if it's a bacteria, you want an antibiotic. But what then happens is actually natural selection. It's normal biology that some of them will mutate and find a way to still grow even in the presence of the antimicrobial, the antibiotic. Those are resistant to that one. And they, these little genes that give them that resistance are often transmissible, not just to their children, but actually to their aunts, uncles, cousins and everyone, by either popping them out into plasma or the liquid around them, or by actually putting out a kind of proboscis and it the genes run along that bridge and different ways. So it's very easy to spread. So if you get resistance to an antibiotic in one bacteria, you'll probably get it moving from that to other bacteria. Now, as I said, in the old days, that was all right because we always had other antibiotics. But no new antibiotics have been discovered and brought into clinical practice since the late 80s. So we've got an empty pipeline. Meanwhile, the resistance is going up and up. And so now at least 700,000 people die every year across the globe of this. And that's only bacteria. 7 to 10% of HIV viruses are resistant to first line bugs. One of the common causes of death in low and middle income countries is TB. Drug resistant TB is now the the TB bug that people catch up front in South Africa and Russia quite often. Extreme drug resistance is becoming prevalent and is really difficult to treat, both in unpleasantness for the patient, but in cost, it multiplies the cost by about 80 times. Malaria is becoming resistant, fungi are becoming resistant, and we have this relatively empty pipeline. So this is a growing pandemic. It's slow growing, but it's happening across the world. And we can take it with us. So wonderful study from Sweden, young people going backpacking, the bugs in their guts, their microbiome, didn't have resistant genes before they went. When they came back, almost all of them had resistant genes in their bowels, which are then transmissible around Sweden and the environment. So it's here, it's natural. Fleming in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech predicted it, and it's killing people. So we've got a lot of work to do.

Dr Rupy: Yeah. And I I always bring come back to this anecdotal experience of mine. I've been practicing medicine for about 11 years now. So in my relatively short medical career, I've witnessed the change in first line antimicrobials massively. I remember having to call up the microbiologist to prescribe a carbapenem during my first year of medicine. And now it's given out without any of those previous barriers. Sometimes prophylactically for certain patients pre-surgery. And this just demonstrates to me the huge shift we've had in the need to utilize antimicrobials that were otherwise under lock and key. And I mean, just on Monday, I had a number of different simple, quote unquote, UTIs that were resistant to the first three antimicrobials that we used. And we're really at a loss because diagnostics is an issue as well. I still have to wait three or four days to get the culture results. I still need to wait for blood culture bottles. And that again leads to the utilization of broad spectrum before we can refine exactly what the microbe is that we're dealing with. So there's a whole bunch of different issues going on.

Dame Sally Davies: Absolutely. And I think in in the UK, we're doing quite well. We've reduced the use of antibiotics in general practice by over 7% over a three-year period. And despite increasing use in hospitals and increasingly complex case mix, we've stayed static in the hospitals till COVID. I mean, we're waiting for all the data to come in from COVID, but it is clear from some studies that most patients who go on ventilators are getting blanket antibiotics. So I am worried about what's going to happen, but time will show.

Dr Rupy: You mentioned one thing there about the discovery or the production of new antimicrobials and how that hasn't changed for a number of decades. What is the issue with the production of new antibiotics? Is it a funding issue? Is it an attractiveness issue for the actual pharmaceutical companies in that they're not as profitable as other medications? Is it a combination of all those things or some other things that I haven't even thought about?

Dame Sally Davies: Well, it's both of those. Um, we pay very little for antibiotics. We have been conditioned that way forever. They're off patent, many of them. That leads to another problem, the security of supply that we could talk about, but there's usually only one factory and when the PipTaz factory burnt down, we had 20% of the supply for 18 months while they rebuilt it. But the problem is, if you don't pay much, then the farmer companies say, this is hard science and then you've got to pay for the clinical trials and the registration and then they back off. So we had across the world to put more money in at the research stage, and we're now looking at, so how do you persuade companies to invest in this area? And I'm really proud because our NHS is leading the way on this with a pilot where we are in the middle of choosing two drugs, one just come onto the market, one coming onto the market, antibiotics, that will be valued in a totally different way. So NHS working with NICE, working with the pharmaceutical companies, they're going to look at the cost of the drug based on its value, not just to an individual patient, as NICE normally does, but to the NHS as a whole, stopping that before it spreads, to the drug kit, you know, is it novel, do we need it, and to society as a whole, because these are global goods and we really need to value them better. And we're doing it by a subscription methodology. So we're going to pay them up to 10 million a year each year for the drug, the antibiotic, which means that then doctors can use them when they really need them and it won't impact on the bottom line of the companies. So they're not piling them high to sell them to make their profit. We've agreed a value for that drug and we'll use it as little as we can.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, I think the current pandemic is really putting that in perspective actually, because it's not just like you said, the previous way in which we've been seeing antibiotics as a product of all the research and that one time use. It's the global value of said products. And you know, the pandemic is really putting into a painting a clear picture as to how we need to value these sorts of medications going forward. Otherwise, you're not going to see the production of them. And and going back to the point you made about how we are using antibiotics in the COVID environment, it is quite worrying actually. I haven't really spoken about it openly, but the way we were seeing patients, giving them antibiotics and then sending them home to prevent the secondary bacterial infection when we had no idea about what the ramifications of that were, you know, it was probably the pragmatic thing to do, but the long-term issue is yet to yet to be seen.

Dame Sally Davies: Yeah. So I'm not criticizing any doctor because when you're faced with a sick patient, you've got to take difficult decisions. But we may be aggravating this slow rising pandemic. I'm talking about it like a lobster. So as a cook, you'll enjoy this one. COVID is the lobster dropped into boiling water and it makes a lot of noise. AMR is the lobster put into cold water and heated up very slowly. It doesn't make any noise and the RSPCA say it's much kinder, but it'll be dead all the same at the end of the day.

Dr Rupy: I'm definitely going to use that analogy. That's that's brilliant. I'll reference you, of course, don't worry. You've been talking a lot about the responsibility of us as users of antimicrobials, but also us as a wider society. I'm wondering if you could sort of give us an idea of the things that we need to do that are within our control that can help prevent this pending pandemic. Obviously, there is a responsibility of government to make this a wider issue, also working with industry. We have to do that to create the antimicrobials in the first place and do the correct R&D. But what can we do as consumers?

Dame Sally Davies: Well, we can do two things as consumers. One as patients, if the doctor says, no, I think this is a virus, don't nag them and demand antibiotics. If the doctor says, I think your child has a virus, but I'll give you a prescription so that if the child gets really sick, you can get it, don't get it unless the child really is sick. And prevent infections. I mean, what are we learning from COVID? Wash your hands while you sing Father Christmas twice or happy birthday, actually 20 seconds. Um, you know, look, prepare your food cleanly, be social distance if you don't need to be closer. But we can do other things as consumers. So there's consumer pull. The Americans have a special chart to mark and they look and announce who is doing well in the fast food business for appropriate use of antibiotics in their food chain in producing the beef, the pork and the chickens. Because of course, some 70% or more of antibiotics go into our food chain, animals mainly and crops, but also fish farming. So go to fast food companies and demand that they stop using antibiotics for growth promotion and prevention and only treat sick animals. And actually, if you have shares, then think about using your shares with the in the through the companies as investor action. Are those companies, banks and other people investing in the food chain in a way that is bad for antibiotic use? Or are they investing in the health sector but not making sure it's an infection proof as far as you can health sector? Or think about sewage, you know, a water company. Are you asking that water company, are they cleaning up the sewage so the 70 to 90% of antibiotics that animals, humans, animals take that gets peed and pooed out is cleaned out of the sewage. So there's the individual preventing infection, not overusing antibiotics, but then as a consumer with fast food restaurants and as an investor.

Dr Rupy: I I want to double click on the the agricultural element of this actually because I think a lot of people don't realise that antimicrobials are used extensively and the majority the majority of antimicrobials are used in the animal industry and what impact that could be having on our food supply chain as well as water supply and all the rest of it, particularly if you live in a country that doesn't have good sanitation systems. Why do we use antimicrobials in food production, animal agriculture? And how does that lead to impacts on antimicrobial resistance in humans?

Dame Sally Davies: So, um, antibiotics are used in the food chain, in animal and protein production and fish farming because it's cheaper than cleanliness. Um, you know, we're very used as humans to washing hands and surfaces and preventing infection by keeping it out. It's called biosecurity in the food chain. They don't want to pay for that. Though actually, when people invest in that, they can usually get a bit more in the market and it usually pays back over time. So we're trying to persuade investment banks to be generous with their loans to develop biosecurity. So that's one big issue there. The other is that it does cause growth promotion because it changes the microbiome. There's very nice work in rats and in pigs that you can transfer the microbiome from a fat animal to a skinny one and the skinny one gets fat. Doesn't work the other way, interestingly. And there's even a court case in the states where a woman was given the microbiome as a fecal transplant for C. diff and she got fat and then she tried to sue. I don't know how it ended up.

Dr Rupy: Oh, really? Wow. I didn't know about that one.

Dame Sally Davies: And that then of course feeds back round to us, because think about obesity and there's a direct correlation between infant and early childhood frequency of antibiotic prescription and obesity. It may be other things. I've only said it's a correlation. So, you know, they use antibiotics in the food chain because it's easier, cheaper, and you get a slightly bigger animal. And we've got to move beyond that. Does it matter to us? Well, it does because they're used indiscriminately and there will be and there is evidence of resistance developing in those animal microbiomes and in those environments that can then spill over to humans. It doesn't happen a lot. The biggest cause of resistance that we encounter that matters to humans happens in the human health system, but it's still there. And do we really want a dirty environment where all of that's going into our water system, our waterways, the rivers, the lakes, the seas, the oceans, and we're steadily poisoning it. It does sound a bit worrying for my grandchildren, I think. It's about planetary health, isn't it?

Dr Rupy: Absolutely. Yeah. And I love the way you always end off your talks with saying, you know, think about your grandchildren, whether you're an investor and I think ESG investments are something that are becoming a lot more, I use the term fashionable loosely, but they're actually becoming very competitive because the returns on those are incredible. So purely from a financial point of view, they are advantageous and they are attractive, but also with the byproduct being improved planetary health, improved human health, they should be looked at as more sustainable options as well. You've given an incredible talk at the Royal Institute a few years ago. It could have been done literally six months ago and it's still absolutely everything you talked about is so current. And there were two things I wanted to to touch on. One was the discovery of the mutant gene that led to antimicrobial resistance in pigs in China that was also found across the world. So just because one country has practices that indiscriminately use antimicrobials doesn't mean that we thousands of miles away are protected from that. And I wonder if you could talk a bit about colistin itself as well and why we might be using that in the agriculture industry at all.

Dame Sally Davies: So colistin, as some of you will know, is a very old antibiotic and it's horrible. It's horrible to take. It has lots of side effects. So having discovered it, shown it works, it was put in the cupboard essentially. So it was picked up and used in animals and this resistance gene that started in China, interestingly, within two years, you could find it in pigs and other places across the world within two years. It shows how quickly these genes can move and it did move into the human population and lead to problems. And it led to problems because we've got resistance in other antibiotics. So therefore, we went back to this old one, colistin, to use it and found that a number of patients were resistant. So not only were they getting something really noxious and with side effects, they were getting something that for many didn't work. But the silver lining coming out of that is that China has now banned colistin for animal use and has said that by the end of the year, antibiotics must be taken out of animal feed. So they have to be prescribed and given. That's the start. I want more, but hey, well done, China. And India's done another big move this year. They've issued draft act for their parliament of what levels are safe in the environment, impacting their generics industry and everything. So, you know, they really are making moves.

Dr Rupy: And what do you make of the the big agricultural bills at the moment? Obviously, can't really talk about this without mentioning the B word, but given we're going to be moving ourselves out of the EU, we're going to lose those protections. We may be vulnerable to less favourable trade deals with other countries, namely America, where they don't have as stringent abattoirs, stringent agricultural methods of production. What are your views on that? And how do we again as consumers make sure that we are choosing or exposing ourselves to the correct products in supermarkets?

Dame Sally Davies: So if we had stayed with the European Commission standards, then I would have no worries. As it is, what I can see is we're going to have to keep educating MPs to these issues about antibiotics and also endocrine disruptors and hormones so that they take a considered opinion. I'm sure we can educate them. I'm sure they'll take the right decisions, but we're going to have to educate them and that will be hard work ongoing.

Dr Rupy: Yeah. Is there, because a lot of people see me, let's say, as a singular person as a doctor with some influence suggesting to people that they should choose products that are antibiotic free, hormone free, of the highest ethical standards as being elitist. It's it's unachievable for most households across the UK. You can't source them in local supermarkets. Why would you suggest that people, especially in the current day and age, should choose those products over other ones that are a lot more affordable? And so what if it's got, you know, these issues with it for them? What do you say to that?

Dame Sally Davies: Well, first, meat can't go into our food chain in Britain if it's still got residues of antibiotics. So what we're interested is not antibiotic free, but antibiotics only used appropriately if an animal was sick. And then it's fine. We don't want sick animals and we do want them cured and then back in coming into the food chain. So it's about appropriate use and organic farms clearly get that and not everyone can afford that. But we do have a very good beef, homegrown beef and pig, lamb industry and most of them use very little antibiotics. Indeed, voluntarily, antibiotic use in the food chain in this country has gone down by over 50% over the last few years. They've really been doing a good job. Once they understood they needed to, they put their minds to do it. But I would also balance on the other side because you talk about food and all of that is most people are eating too much meat. So, you know, we could have less animal protein, pay the same, and just eat less of it and we would be healthier as a general population measure.

Dr Rupy: In terms of the different things, from what I understand and from the report that you sent me earlier actually before our conversation, human behaviour, water cleanliness, the corporate environment as well as animal production and food, these are incredibly important to the fight against antimicrobial resistance. When it comes to producing crops and foods, are there any things that we need to be aware of from that perspective as well?

Dame Sally Davies: Well, yes, we've got horror stories there too. Um, let me try. Did you know that most of the citrus fruits in California and Florida are sprayed with streptomycin, the last line drug for TB?

Dr Rupy: Oh my word. Wow. No, I had no idea about that one.

Dame Sally Davies: Meanwhile, some citrus trees in Asia are injected with amoxicillin and some date palms in the middle of East are injected with antibiotics. So yes, there is, let alone the antifungals sprayed around. There is a problem in some of this.

Dr Rupy: Wow. And what would the reason be? Is it because they're rife with with microbes that jump from from different plants or?

Dame Sally Davies: They have various infections that respond to these preventive measures. And so we really need to start either breeding trees or using CRISPR or whatever to get the plants that are resistant to that infection rather than using the antibiotics and antifungals.

Dr Rupy: We've talked a bit about the sort of the negative stories, I guess. What are you most optimistic about over the next five to 10 years?

Dame Sally Davies: Well, I do think we will, in part, probably thanks to COVID giving some momentum, get a treaty on some of this within 10 years. I think that we are making moves to stimulate drug companies to move forward so much so that they announced recently, excitingly, a billion dollar fund from the pharma companies themselves to invest in bringing up to four drugs, new antibiotics into use. And I think governments are beginning to understand what matters. We clearly need to help the low and middle income countries more with their surveillance and building, you know, sanitation and really upping their health systems and their food chain systems. But that's beginning to happen and as countries develop, they get stronger at all of this. So I am optimistic. I'm a glass half full that we can make this better.

Dr Rupy: This is such a fascinating conversation and I I I really do feel the optimism from your side as well. And I think given the fact that we are going through a pandemic at the moment, I feel that it's brought to a lot of our attention what can happen when things go wrong. And when you have predictions like, you know, in 2050, it's going to cost 4% of the global GDP, that's palpable today because we recognise just how impactful a pandemic can be on the economy. And so I I I believe that this will, you know, again be one of those features that we can work on collaboratively across different nations to to to address it. So.

Dame Sally Davies: I pray we can, but I also believe it. Yeah.

Dr Rupy: Great. Great. Dame Sally, I'm going to leave it there because I feel like the connection's a little bit raggedy, but I would love, honestly, I would love to prepare a meal for you. If I was going to prepare a meal, what what what would you want me to cook?

Dame Sally Davies: Oh, well, why not do something vegetarian from your own ethnic, your parents' food?

Dr Rupy: Yeah. I'd I'd make a chickpea curry with amchur, mustard seed, fennel seed, and a little bit of spinach as well. I think that would be a good one.

Dame Sally Davies: I'll be along. Can I bring my husband because he'd love it too.

Dr Rupy: Of course. Of course. Absolutely. Thank you for listening to the Doctor's Kitchen podcast. If you enjoyed this episode, please do make sure you subscribe on iTunes and leave us a review. For more information on how to live a healthier and happier life, check out the doctorskitchen.com.